De kapel van het Heilig Sacrament en van de Zoete Naam Jezus en het Heilig Kruisaltaar

Kerkelijke samenspraak over het Heilig Sacrament

Pieter Paul Rubens, ca. 1609, Kapel H. Sacrament

Titel kunstwerk:

Kerkelijke samenspraak over het H. Sacrament

(of Disputa over het Heilig Sacrament,

of De verheerlijking van de Heilige Eucharistie)

BELLORI 1672:

Bellori duidt in 1672 het schilderij op het Sacramentsaltaar aan als: ‘In San Domenico nell’altare del Sacramento li quattro Dottori, che parlano del Divino pane.’: te lezen als: ‘De vier kerkvaders die zich onderhouden over het goddelijke brood’.

BAUDOUIN Frans, Pietro Paolo Rubens, (Mercatorfonds) Antwerpen, 1977: p. 74:

In de Sint-Pauluskerk bevindt zich nog een tweede werk dat eveneens de stijlkenmerken vertoont uit de eerste jaren van Rubens’ terugkeer uit Italië. Reeds in 1672 vermeldde Bellori het als één der eerste schilderijen die de kunstenaar toen schilderde. Vaak wordt het De Disputa genoemd. Beter kan het De Verheerlijking van de Heilige Eucharistie worden betiteld, tenzij men De Realityt van den Heylighen Sacrament zou verkiezen, zoals het opgetekend werd in de inventaris van de bezittingen van de Broederschap van de ‘H. Sueten Naem Jhesus en den H. Sacramente’, opgesteld op 24 juli 1616. Ongetwijfeld geeft deze titel het best de intenties weer van dezen die het werk hebben laten schilderen. Inderdaad, de kerkvaders en godgeleerden die er op afgebeeld zijn stellen zich a.h.w. ‘garant’ voor die ‘realiteyt”: Christus’ waarachtige aanwezigheid in het H. Sacrament, een rooms-katholiek geloofspunt, dat door de protestanten werd aangevochten.

KNIPPING 1939-1940:

Raphaels Verheerlijking van het H. Sacrament in het Vaticaan heette al vroeg ‘Disputà’, ofschoon er van een eigenlijk twistgesprek niet veel getoond wordt. Onder die benaming droeg Giorgio Ghisi in 1552 een prent naar de muurschildering op aan Gravelle. Geïnspireerd door de Urbinaat graveerde Cornelis Cort te Rome (1575) een dispuut der kerkvaders over de eucharistie; soortgelijke voorstelling schildert Abraham Bloemaert voor de Keulse (prent van Cornelis Bloemaert; 1629) en Rubens voor de Antwerpse Sint-Pauluskerk. Staan op het eerste werk drie der Latijnse kerkvaders rustig met elkaar te redeneren, terwijl Ambrosius de toeschouwer op de tentoongestelde monstrans wijst, in het altaarstuk van Rubens wordt het een waarachtig godsdienstgesprek, waarbij in het voorplan twee figuren schier onverholen Luther en Calvijn aanduiden, die hun tegenstanders bijbelplaatsen schijnen voor te leggen. Daar het stuk voor een dominicanenkerk bestemd was, ontbreekt natuurlijk Sint Thomas van Aquino niet. ’t Tekent wel dat dit werk ten tijde van de Antwerpse meester de ‘Realiteyt vanden Heyligen Sacramente’ genoemd werd.’ … Op Rubens’ tapijtenreeks triomfeert de katholieke kerk dóór de H. Eucharistie en vooral de Zege van de Waarheid belijdt duidelijk de leer der waarachtige Tegenwoordigheid tegenover nieuwgezinden.

MANNAERTS Rudi, Sint-Paulus. De Antwerpse dominicanenkerk, Antwerpen, 2014: p. 75:

Het schilderij wordt in 1616 De realiteit van het Heilig Sacrament genoemd, met andere woorden: De reële tegenwoordigheid van Christus in het Heilig Sacrament. De aan het Italiaans ontleende term ‘dispuut’, waaronder dit schilderij bekend staat, is hier niet zozeer op te vatten als discussie bij een meningsverschil, maar als een samenspraak van gelijkgezinde katholieken die zoeken naar argumenten om dit geloofspunt over de Eucharistie te staven. Dat het evenmin om een vrome aanbidding van het Sacrament gaat, maar om een intellectuele dialoog, eigen aan de scholastieke traditie, wordt duidelijk gemaakt door de gesticulaties van gezaghebbende geleerden en kerkelijke ambtsdragers: ‘vingers worden opgestoken, wijzen, benadrukken, weerleggen en sommen de argumenten op’.

Type kunstwerk: schilderij

Kunstenaar:

- Pieter Paul Rubens (1577-1640)

- Onderstuk door Antonius Goubeau (1616-1698). Zie: Verdere geschiedenis

Datering: ca. 1609

– Eén der eerste werken van Rubens in Antwerpen na zijn terugkeer uit Italië:

DE MONCONYS 1666:

Au droit est un tableau de Rubens, des Docteurs de l’Eglise.

MULLER 2004 (in HECK, Le Rubénisme en Europe ..):

De beschrijving van DE MONCONYS (1666): ‘On the left is a ‘perfectly beautiful painting by Caravaggio of a Virgin seated upon a throne, holding her Jesus who is nude, to whom two saints of the order present diverse personages. On the right there is a painting by Rubens of the Doctors of the Church.’

BELLORI 1672:

Bellori kwalificeert het schilderij als ‘één der eerste werken van Rubens in Antwerpen’: “Fra Le Prime Ch’Egli Dipingesse In Anversa”

ROOSES 1886-1892:

L’œuvre date des premiers temps après le retour de Rubens d’Italie. Exécutée probablement en 1609, elle précèderait l’Erection de la Croix. La sécheresse des tons et la disproportion entre les figures des divers plans se retrouvent dans les volets de ce dernier triptyque. Quelqu’invraisemblable que cette opinion puisse paraître, le tableau nous semble entièrement peint de la main de Rubens.’

VLIEGHE 1972 (Corpus Rubenianum):

This altar-piece is generally dated shortly after Rubens’s return from Italy, c. 1609. One of the earliest records of it, that of Bellori in 1672, says that it was “fra le prime ch’egli [sc. Rubens] dipingesse in Anversa” . Stylistically it resembles The Adoration of the Magi, now in the Prado (K.d.K., p. 26), which documentary evidence shows to have been painted in 1609-10. Als Oldenbourg pointed out, the somewhat elongated figures are typical of the earliest Antwerp paintings (Oldenbourg, 1922, p. 73); they also recall Rubens’s latest Italian works such as the first altar-piece for Santa Maria in Vallicella, now in the Grenoble Museum (11, No. 109).

The present panel, executed for the altar of the Holy Sacrament chapel in the Antwerp Dominican church, is probably one of the works by Rubens referred to as “diversche Stucken … die in groote extime gehouden worden als namentlyck … tot… Preeckheren die fray syn”, in a letter of 12 March 1611 from Jan le Grand in Antwerp to his colleague Lieven vuytten Eeckhoute at Dunkirk (published by A. Monballieu in P.P. Rubens en het “Nachtmael” voor St.-Winoksbergen ( 1611) , een niet uitgevoerd schilderij van de meester, Jaarboek Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerpen, 1965, p. 196).

BAUDOUIN Frans, Pietro Paolo Rubens, (Mercatorfonds) Antwerpen, 1977:

- 76: Ook in dit altaarstuk is de band met Italië nog duidelijk zichtbaar. De ietwat uitgelengde figuren op de voorgrond, hun bruinig incarnaat, het Venetiaans groen-blauw op de achtergrond, de sterke architecturale accenten die aan de compositie een vaste structuur verlenen zijn alle elementen die dit werk nog gemeen heeft met taferelen die Rubens tegen het einde van zijn verblijf in Italië, in de jaren 1606-1608, had geschilderd. De putti die in de wolken boven de groepen kerkvaders en theologen zweven zijn tweelingbroertjes van die welke op het doek te Grenoble en in de taferelen in het koor van Santa Maria in Vallicella te Rome worden aangetroffen.

- 308: Vermoedelijk rond dezelfde tijd [enkele maanden na zijn aankomst te Antwerpen] schilderde hij voor de broederschap van het Heilig Sacrament in de dominicanerkerk te Antwerpen (nu Sint-Paulus) het altaarstuk De Verheerlijking van de Heilige Eucharistie.

WUYTS 1992 (Kwintet):

Tot de eerste werken welke Rubens na zijn terugkeer uit Italië eind 1608 te Antwerpen schilderde, behoort het altaarstuk dat hij voor de leden van de Sodaliteit van den H. Sueten Naem Jhesus en den H. Sacramente uitvoerde ter versiering van hun altaar in de Sacramentskapel van de Dominicanenkerk. Reeds in 1672 schreef G.P. Bellori in zijn Le vite de’ pittori, scultori ed architetti moderni dat dit stuk dient geplaatst te worden ‘fra le primi ch’egli dispingessse in Anversa’. Deze mededeling wordt trouwens bevestigd door het stijlkritisch onderzoek, dat het werk 1609-1610 dateert.

MANNAERTS Rudi, Sint-Paulus. De Antwerpse dominicanenkerk, Antwerpen, 2014: p. 75:

Ca. 1609 bestellen de dominicanen bij Pieter Paul Rubens dit altaarstuk en de twee predellastukken Mozes en Aäron. […] De maniëristische, ietwat uitgelengde figuren zijn typisch voor Rubens’ beginperiode.

Stijl: barok, zie ook: onder ‘datering’

Materiaal: olieverf op paneel

Afmetingen:

– 377 x 246 cm. (bron: inventaris SIRJACOBS, MANNAERTS 2014, Donnet)

– 377 x 248 cm. (bron: Rubensonline)

– 309 x 241,5 cm. (bron: VLIEGHE, Corpus Rubenianum, 1972)

https://rkd.nl/nl/explore/images/record?query=rubens+disputa&start=0 )

Zie: verdere geschiedenis

Inventarisnr.:

SIRJACOBS Raymond, Sint-Paulus-Info, nr. 70, Inventaris van het patrimonium van de Antwerpse Sint-Pauluskerk, dl. I, 2006: p. 1807, nr. E21.

PA.029.E0481 (Donnet)

Locatie: Kapel van het Heilig Sacrament en van de Zoete Naam Jezus

ROOSES 1886-1892:

Le tableau fut fait pour l’église où il se trouve encore à sa place primitive. Il est déjà mentionné, en 1616, dans un inventaire des ornements et meubles appartenant à la chapelle du nom de Jésus et du St. Sacrement.

MANNAERTS Rudi, Sint-Paulus. De Antwerpse dominicanenkerk, Antwerpen, 2014: p. 75-78:

Het altaar met de Kerkelijke samenspraak over het Heilig Sacrament

(Pieter Paul Rubens, ca. 1609)

Ca. 1609 bestellen de dominicanen bij Pieter Paul Rubens dit altaarstuk en de twee predellastukken Mozes en Aäron. Naar aanleiding van het nieuwe koordoksaal met twee zijaltaren wordt in 1654–1656 het barokke Sacramentsaltaar opgetrokken door Peter i Verbruggen. Uit esthetische (en andere?) motieven is het nieuwe altaar – aldus het contract – opgevat als een pendant van het tegenoverliggende Maria-altaar, dat vier jaar eerder is aangevat. Om netjes in dit portiekaltaar te passen wordt Rubens’ paneel in 1680 vergroot, vooral onder- en bovenaan, maar ook een weinig in de breedte (tot 377 x 246 cm). Het schilderij wordt in 1616 De realiteit van het Heilig Sacrament genoemd, met andere woorden: De reële tegenwoordigheid van Christus in het Heilig Sacrament. De aan het Italiaans ontleende term ‘dispuut’, waaronder dit schilderij bekend staat, is hier niet zozeer op te vatten als discussie bij een meningsverschil, maar als een samenspraak van gelijkgezinde katholieken die zoeken naar argumenten om dit geloofspunt over de Eucharistie te staven. Dat het evenmin om een vrome aanbidding van het Sacrament gaat, maar om een intellectuele dialoog, eigen aan de scholastieke traditie, wordt duidelijk gemaakt door de gesticulaties van gezaghebbende geleerden en kerkelijke ambtsdragers: ‘vingers worden opgestoken, wijzen, benadrukken, weerleggen en sommen de argumenten op’. De maniëristische, ietwat uitgelengde figuren zijn typisch voor Rubens’ beginperiode.

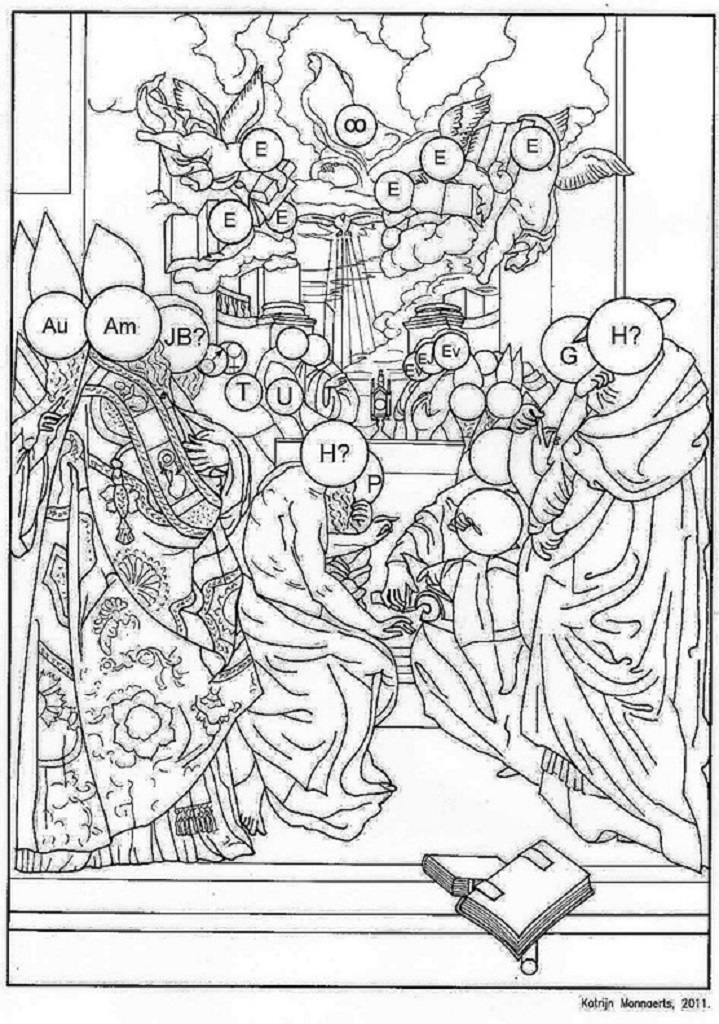

God de Vader (∞), in hemels zachte kleuren van wit, roze en geel, en de zinnebeeldige duif van de Heilige Geest in het bovenste register onderlijnen Jezus’ reële aanwezigheid in de geconsacreerde hostie. Dartele engeltjes (E) houden de Bijbelboeken open op zinsneden van het Nieuwe Testament die de fundering vormen voor de realiteit van Jezus’ aanwezigheid in de Eucharistie, maar opdat de toeschouwer de tekst vanop grote afstand zou kunnen lezen, is er per regel meestal slechts één lettergreep afgebeeld.

Uiterst links: Caro mea vere est cibus, et sanguis meus vere [est] pot[us] (= Joh. 6:56; mijn vlees is echt voedsel en mijn bloed is echte drank). Midden links en midden rechts wordt dit vrijwel herhaald: Hoc est corpus meum, quod pro vobis datur (Lc. 22:19: Dit is mijn Lichaam, dat voor u gegeven wordt). En uiterst rechts: accipite et comedite: hoc est corpus meum (Mt. 26:26–27: Neemt en eet, dit is Mijn lichaam). Bovendien zet Rubens dit geloofspunt extra in de verf door de opbouw en de kleuren. De ruitvormige compositie moet een spanningsveld creëren rondom de witte hostie, die gevat in een gotische cilindermonstrans, niet enkel iconografisch in het middelpunt van de belangstelling staat, maar aanvankelijk, vóór de vergroting van het paneel in 1680, ook formeel geheel centraal stond.

De bovennatuurlijke dimensie in het tastbare Heilig Sacrament wordt beklemtoond doordat de witte hostie afsteekt tegen het hemelse, blauwe middenveld. Dat blauw wordt in de kleurencompositie geflankeerd door de beide figuren op de voorgrond: links in een gouden koormantel, rechts in het kardinaalsrood. Zo wordt de trits van de hoofdkleuren netjes driehoekmatig verdeeld.

Ten tijde van de contrareformatie wil de katholieke Kerk haar visie, ook over de eucharistie, funderen tegenover de protestanten door een beroep te doen op gezagvolle theologen uit de, onverdachte, eerste eeuwen van het christendom. Daarom treden de vier grote westerse kerkvaders op de voorgrond. De twee bisschoppen, met een gouden damasten koormantel, links, zijn Ambrosius (Am), vooraan, als oudste, die het hoofd wendt naar de tweede, zijn leerling Augustinus (Au) achter hem. Als hun volwaardige tegenhanger staan rechts een kardinaal, mogelijk Hiëronymus, in een bedachtzame houding, en een monnik in zwart benedictijnenhabijt, mogelijk paus Gregorius i de Grote (G?), die eerst kloosterstichter en abt was. Maar als er een oude heilige man halfnaakt bij is (H?), dan is het wel Hiëronymus als boeteling in de woestijn, die dan echter wel steevast een kardinaalsrode mantel bij zich heeft. In dat geval zou de kardinaal rechts de geleerde Sint-Bonaventura zijn. Mag de zwartharige man achter Ambrosius worden vereenzelvigd met Johannes de Doper, die in de woestijn helemaal niet bekommerd was om een fijn uiterlijk en Christus aanwees als het ‘Lam Gods’ (de aanspreking bij uitstek van Jezus, als aanwezig in de hostie van de communie)? Achter de halfnaakte man, trekt de man met het langwerpige kale hoofd, bedachtzaam aan zijn baard en neemt notities; hij heeft veel weg van Sint-Paulus (P). In dat geval verwijst zijn schrijfactiviteit naar de oudste uiteenzetting van het Laatste Avondmaal en naar de oudste formulering van de Eucharistie, namelijk in zijn Eerste Brief aan de Korintiërs (11:23–39). De paus, met de gouden tiara, is Urbanus iv (U), die door toedoen van de Luikse begijn, de heilige Juliana van Cornillon (♀), achter hem, in 1264 het feest van het Heilig Sacrament instelt: ‘Corpus Christi’. Hij is in een conversatie gewikkeld met de grote dominicaner theoloog Thomas van Aquino (T), die herkenbaar is aan de gouden kralenkrans ter hoogte van zijn borst. Onder de overige geestelijken in verschillend habijt, is er nog een dominicaan. De baardloze jonge man in toga, gekleed in het rood, is Johannes de Evangelist. Zijn beide buren zijn vermoedelijk ook evangelisten.

In 1794 voeren de Franse Revolutionairen Rubens’ schilderij als oorlogsbuit mee naar Parijs. In 1815 keert het altaarstuk weer naar Antwerpen, in 1816 naar zijn oorspronkelijke plaats.

- (de originele) compositie (ook qua kleuren)

ROOSES 1886-1892:

La composition du tableau, étudiée et maniérée, manque complètement d’unité. Les quatre docteurs du premier plan sont entièreement isolés, de même que les groupes à droite et à gauche. Ce manque de liaison est encore accentué par le défaut de proportion entre les différents groupes. Sur le devant, les figures sont énormes, imposantes et lourdement drapées; celles du fond n’ont pas le quart de la grandeur naturelle et semblent des poupées inanimées, sans que la perspective donne la raison de cette différence. Il en est de même des couleurs, riches et pleines au premiers plan, morcelées et pâles le fond. Même dans les draperies des personnages la discordance règne; les uns portent des vêtement d’église fort riches, les habits des autres ont la simplicité du couvent. Par une fiction hasardée, St. Jérome est vêtu comme un habitant du désert; il a le buste nu et un morceau d’étoffe est étendu sur les genoux. Le groupe de Dieu le père et des anges qui l’environnentest d’une pâleur excessive, les chairs d’un rouge de brique désagréable. Il y a certes parmi les prélats, au premier plan, de nobles figures qui ne seraient pas déplacées dans les œuvres capitales de Rubens, mais elles ne compensent pas le manque d’unité dans la composition et dans l’exécution.

Le tableau est fait avec un soin extrême, les grandes figures sont peintes minutieusement. Nulle part, on ne remarque des retouches; une même main semble avoir exécuté l’œuvre dans toutes ses parties. Dans son ensemble, le coloris est sec et dur, les ombres sont trop noires et trop opaques, l’inspiration et l’entrain manquent.

VLIEGHE 1972 (Corpus Rubenianum):

The arrangement of the figures round the altar, as in an exedra, is clearly based on Raphael’s famous Disputa in the Vatican [K.d.K., Raffael, p. 60); St. Jerome’s attitude on the right of Rubens’s composition reflects that of the figure on the left of Raphael’s fresco. As regards the general composition, Rubens also seems indebted to another work by Raphael, the dimensions of which are more similar to the present one than those of the Disputa: viz. The St. Cecilia, now in the Pinacoteca Nazionale at Bologna but originally in the church of San Giovanni in Monte in that city [K.d.K., Raffael, p. 117). The figure of St. Paul on the left of that painting, leaning his head meditatively on his right hand, performs the function of a frame to the composition in a way closer to that of Rubens’s St. Jerome than does the corresponding figure in the Disputa. In the old, half-naked man in the middle distance we may recognize the Seneca motif: this famous Hellenistic work was copied by Rubens (G. Fubini and J.S. Held, Padre Resta’s Rubens Drawings after Ancient Sculpture, Master Drawings, 11, 1964, p. 130, fig. 7) and inspired his Death of Seneca in the Alte Pinakothek at Munich [K.d.K., p. 44), which was painted at about the same time as the present work.

[…]

The altar-piece has not been preserved in its original State. A comparison with Hendrik Snyers’s engraving of 1643 shows differences of detail and in the relation of its height to its width. The projection seen in the engraving under St. Gregory and St. Jerome has been replaced by two books. We also see that in the painting the raised platform has been enlarged so that its edge is in line with the original projection. Changes were also made in the upper part of the picture: e.g. the figure of God the Father is less close to the upper edge than it is in the engraving, and the floating part of the Father’s mantle looks longer. Finally, the picture would seem to have extended less far to either side than it does now, as in the engraving the figures of saints are slightly cut off by the border.

LAWRENCE 2000 (St.-Paulus-Info):

Based on Raphael’s Disputà, a work Rubens knew initially from Northern and Italian engravings, and which he subsequently encountered first-hand in Rome during his Italian sojourn (1600-1608), the Real Presence depicts a fictive council, convened in the presence of the Trinity, inside a ravaged edifice thought to represent the institution of the Church in the Spanish Netherlands at the time the panel was commissioned. In the lower register an assembly of church fathers, saints, theologians and other holy witnesses is arranged around an altar surmounted by a cylinder monstrance, containing the consecrated Host the panel’s formal and iconologic focus. Just as the figures in Raphael’s assembly those in Rubens’ council are depicted in pairs, involved in a spirited defense of Transubstantiation — the miraculous transformation of the(water and wine into the body and blood of Christ. In the upper register is a depiction of God and the Holy Spirit (shown as a dove),” to either side of which are clusters of putti holding open books.

MANNAERTS Rudi, Sint-Paulus. De Antwerpse dominicanenkerk, Antwerpen, 2014: p. 77:

Bovendien zet Rubens dit geloofspunt extra in de verf door de opbouw en de kleuren. De ruitvormige compositie moet een spanningsveld creëren rondom de witte hostie, die gevat in een gotische cilindermonstrans, niet enkel iconografisch in het middelpunt van de belangstelling staat, maar aanvankelijk, vóór de vergroting van het paneel in 1680, ook formeel geheel centraal stond.

De bovennatuurlijke dimensie in het tastbare Heilig Sacrament wordt beklemtoond doordat de witte hostie afsteekt tegen het hemelse, blauwe middenveld. Dat blauw wordt in de kleurencompositie geflankeerd door de beide figuren op de voorgrond: links in een gouden koormantel, rechts in het kardinaalsrood. Zo wordt de trits van de hoofdkleuren netjes driehoekmatig verdeeld.

- De opschriften over het Heilig Sacrament op de banderollen van de engelen

ROOSES 1886-1892:

Le lieu où la scène se passe est un édifice de fantaisie, en marbre, dont on ne voit que deux colonnes sur les cotés et un hémicycle en ruines dans le fond. Ce dernier s’ouvre au milieu sur le ciel d’un bleu vif parsemé de légers nuages.

Dans le haut du tableau on voit Dieu le Père planant dans un gloire. I lest entouré de six anges qui volent dans les airs en tenant des livres ouverts, dans lesquels on lit des textes se rapportant au Sacrement de l’Eucharistie. Au-dessous de Dieu le Père, le Saint Esprit darde ses rayons sur l’assemblée.

MANNAERTS Rudi, Sint-Paulus. De Antwerpse dominicanenkerk, Antwerpen, 2014: p. 75, 77:

Dartele engeltjes (E) houden de Bijbelboeken open op zinsneden van het Nieuwe Testament die de fundering vormen voor de realiteit van Jezus’ aanwezigheid in de Eucharistie, maar opdat de toeschouwer de tekst vanop grote afstand zou kunnen lezen, is er per regel meestal slechts één lettergreep afgebeeld.

Uiterst links: Caro mea vere est cibus, et sanguis meus vere [est] pot[us] (= Joh. 6:56; mijn vlees is echt voedsel en mijn bloed is echte drank). Midden links en midden rechts wordt dit vrijwel herhaald: Hoc est corpus meum, quod pro vobis datur (Lc. 22:19: Dit is mijn Lichaam, dat voor u gegeven wordt). En uiterst rechts: accipite et comedite: hoc est corpus meum (Mt. 26:26–27: Neemt en eet, dit is Mijn lichaam).

IDENTIFICATIE VAN DE KERKELIJKE FIGUREN

Legende:

Am: Ambrosius

Au: Augustinus

E: engelen

Ej: Johannes de Evangelist

Ev: evangelisten

G?: Gregorius I de Grote

H?: Hiëronymus

JB: Johannes de Doper

P: Sint-Paulus

T: Thomas van Aquino

U: paus Urbanus IV

∞: God de Vader

♂: man

♀: heilige Juliana van Cornillon

- De vier westerse kerkvaders, die op de voorgrond het geheel flankeren

BELLORI 1672:

Bellori duidt in 1672 het schilderij op het Sacramentsaltaar aan als: ‘In San Domenico nell’altare del Sacramento li quattro Dottori, che parlano del Divino pane.’: te lezen als: ‘De vier kerkvaders die zich onderhouden over het goddelijke brood’.

ROOSES 1886-1892:

Devant la table au premier plan, sont assis quatre théologiens; parmi eux on remarque St. Jérôme, un vieillard au buste nu et à la barbe longue; vis-à-vis de lui, deux religeux dont l’un se sert de lunettes pour lire dans un livre que tient sons voisin. A droite et à gauche, contre le bord du tableau, de fortes et imposantes figures sont debout.

VLIEGHE 1972 (Corpus Rubenianum):

The identification of the figures presents some difficulty. The imposing personages in the foreground are certainly the four Latin Doctors of the Church. … These four Saints play a dominant role in this composition, by virtue of the authority the enjoyed among later generations of divines as expounders and defenders of the Eucharistic doctrine.

WUYTS 1992 (Kwintet):

Over de zin van de voorstelling worden we expliciet ingelicht door de inventaris van 245 juli 1616 van de bezittingen van hoger genoemde sodaliteit. Daarin wordt het altaarstuk immers genoemd: “Een constich stuck schilderije van den Heyligen Sacramente, geschildert bij mijnheer Peeter Paulo Rubbens”. Uit deze omschrijving kan men afleiden dat in de verzamelde geestelijken de kerkvaders en theologen uitgebeeld zijn, die in de loop der voorbije eeuwen met klem het dogma van de transsubstantiatie hebben verdedigd tegen de dwaalleer der scheurkerken. Helaas zijn zij niet allemaal te herkennen.

LAWRENCE 2000 (St.-Paulus-Info):

In the foreground are monumental figures of the four fathers of the Western Church, all of whom wrote in defense of Transubstantiation.

MANNAERTS Rudi, Sint-Paulus. De Antwerpse dominicanenkerk, Antwerpen, 2014: p. 77:

Ten tijde van de contrareformatie wil de katholieke Kerk haar visie, ook over de eucharistie, funderen tegenover de protestanten door een beroep te doen op gezagvolle theologen uit de, onverdachte, eerste eeuwen van het christendom. Daarom treden de vier grote westerse kerkvaders op de voorgrond.

- Am en Au: Ambrosius en Augustinus

ROOSES 1886-1892:

A gauche, ces ont deux évêques coiffés de la mitre, St. Ambroise et St. Augustin, causant ensemble, tous deux vêtus de riches chasubles, couvertes de lourdes broderies en or; à côté d’eux, un homme, tête nue, lève au ciel des regards extatiques. A droite, un cardinal, vêtu de son ample robe de pourpre, coiffé de son chapeau, écoute dans une attitude pensive l’argumentation d’un moine debout à coté de lui. Deux livres se trouvent sur les degrés conduisant à l’estrade où sont assis les pères de l’église.

VLIEGHE 1972 (Corpus Rubenianum):

The mitred bishops on the left must be St. Augustine and St. Ambrose, though they are not provided with attributes to indicate which is which.

WUYTS 1992 (Kwintet):

De imposante figuren op de voorgrond zijn ongetwijfeld de Latijnse kerkleraars St.-Augustinus en St.-Ambrosius in de persoon van de gemijterde bisschoppen links, St. Hiëronymus in de persoon van de halfnaakte grijsaard in het midden, de kaalgeschoren Gregorius de Grote en kardinaal Isidorus van Sevilla aan de rechterkant.

LAWRENCE 2000 (St.-Paulus-Info):

On the left is St.Augustine, who inclines towards his, former teacher, St.Ambrose, …

MANNAERTS Rudi, Sint-Paulus. De Antwerpse dominicanenkerk, Antwerpen, 2014: p. 75:

De twee bisschoppen, met een gouden damasten koormantel, links, zijn Ambrosius (Am), vooraan, als oudste, die het hoofd wendt naar de tweede, zijn leerling Augustinus (Au) achter hem.

- G? en H?: paus Gregorius I de Grote en Hiëronymus

VLIEGHE 1972 (Corpus Rubenianum):

In the right foreground is St. Gregory the Great, shown according to custom with shaven head, and St. Jerome in cardinal’s robes.

WUYTS 1992 (Kwintet):

De imposante figuren op de voorgrond zijn ongetwijfeld de Latijnse kerkleraars St.-Augustinus en St.-Ambrosius in de persoon van de gemijterde bisschoppen links, St. Hiëronymus in de persoon van de halfnaakte grijsaard in het midden, de kaalgeschoren Gregorius de Grote en kardinaal Isidorus van Sevilla aan de rechterkant.

LAWRENCE 2000 (St.-Paulus-Info):

…while on the right, St.Jerome attentively listens to the argument of St.Gregory the Great.

MANNAERTS Rudi, Sint-Paulus. De Antwerpse dominicanenkerk, Antwerpen, 2014: p. 77-78:

Als hun volwaardige tegenhanger staan rechts een kardinaal, mogelijk Hiëronymus, in een bedachtzame houding, en een monnik in zwart benedictijnenhabijt, mogelijk paus Gregorius i de Grote (G?), die eerst kloosterstichter en abt was. Maar als er een oude heilige man halfnaakt bij is (H?), dan is het wel Hiëronymus als boeteling in de woestijn, die dan echter wel steevast een kardinaalsrode mantel bij zich heeft. In dat geval zou de kardinaal rechts de geleerde Sint-Bonaventura zijn.

- Tweede groep van vier figuren die met elkaar converseren, centraal voor het altaar

VLIEGHE 1972 (Corpus Rubenianum):

In the middle distance, in the centre of the picture, are four more figures, none of whom can be identified.

Rubensonline:

De vier druk disputerende figuren op het tweede plan zijn niet identificeren, en dit geldt ook voor het merendeel van de geestelijken verder op de achtergrond.

- JB?: Man met baard en zwart haar: Sint-Paulus? , Johannes de Doper?, Mozes?

- Sint-Paulus:

VLIEGHE 1972 (Corpus Rubenianum):

On the left, beside St. Augustine and St. Ambrose, is a bearded figure with long black hair: this may be St. Paul, who was the patron of the Dominican church at Antwerp and to whom we owe the oldest account of the Last Supper, other than that in the Synoptic Gospels (I Cor. 11:23 et seqq.).

WUYTS 1992 (Kwintet):

De zwartharige man met de baard naast Augustinus en Ambrosius is misschien St.-Paulus, patroonheilige van de dominicanenkerk, aan wie de theologie de oudste formulering dankt van het eucharistisch mysterie (1 cor. 11:23-29).

RubensOnline:

De man met de langere donkere baard is waarschijnlijk de H. Paulus, de patroonheilige van de kerk.

- Mozes:

LAWRENCE 2000 (St.-Paulus-Info):

To the right of Ambrose is a black-robed figure with long curling hair and beard who I believe represents Moses: his inclusion in the Real Presence, as well as his pairing with Ambrose, would seem to be appropriate given Ambrose’s discussion of Moses’s transmutation of several substances as a prefiguration of the miraculous transformation of the Eucharistic elements.

MANNAERTS 2018:

Gezien de titel ‘Kerkelijke samenspraak over het H. Sacrament’ is een afbeelding van een outtestamentische figuur zoals Mozes niet aannemelijk.

- Johannes de Doper:

MANNAERTS Rudi, Sint-Paulus. De Antwerpse dominicanenkerk, Antwerpen, 2014: p. 78:

Mag de zwartharige man achter Ambrosius worden vereenzelvigd met Johannes de Doper, die in de woestijn helemaal niet bekommerd was om een fijn uiterlijk en Christus aanwees als het ‘Lam Gods’ (de aanspreking bij uitstek van Jezus, als aanwezig in de hostie van de communie)?

- P: Paulus?

VLIEGHE 1972 (Corpus Rubenianum):

In the middle distance, in the centre of the picture, are four more figures, none of whom can be identified.

MANNAERTS Rudi, Sint-Paulus. De Antwerpse dominicanenkerk, Antwerpen, 2014: p. 78:

Achter de halfnaakte man, trekt de man met het langwerpige kale hoofd, bedachtzaam aan zijn baard en neemt notities; hij heeft veel weg van Sint-Paulus (P). In dat geval verwijst zijn schrijfactiviteit naar de oudste uiteenzetting van het Laatste Avondmaal en naar de oudste formulering van de Eucharistie, namelijk in zijn Eerste Brief aan de Korintiërs (11:23–39).

Figuren rond het altaar:

- U, ♀ en T: Paus Urbanus IV, Sint-Juliana van Cornillon, Thomas van Aquino

ROOSES 1886-1892:

Dans la partie inférieure, un ostensoir est placé sur une table couverte d’un linge blanc. Derrière cette table, on aperçoit une douzaine d’ecclésiastiques, parmi lesquels on distingue deux évêques, un pape, St. Thomas d’Aquin et différents autres religieux peints dans des proportions fortement diminuées.

VLIEGHE 1972 (Corpus Rubenianum):

St. Thomas Aquinas, recognizable by the sun on his breast, is seated behind the altar on the left, in conversation with a pope.This is certainly Urban IV, who instituted the Eucharistic feast of Corpus Christi by a bull of 1264; the tekst of the Office wit hits hymns was composed by St. Thomas (E. Schoutens, Histoire du culte de la très Sainte Eucharistie en Belgique, Antwerp, 1886, p. 133-147.) Two mitred bishops are seated behind the altar on the right.

WUYTS 1992 (Kwintet):

Links achter het altaar zitten een dominicaan en een paus in gesprek. In hen herkennen we Urbanus IV, die in 1264 het feest van Corpus Christi instelde, en Thomas van Aquino, die voor dit feest de tekst en de hymnen voor het officie schreef.

LAWRENCE 2000 (St.-Paulus-Info):

Seated to the left of the altar, in an area only vaguely indicated in the panel’s modello, but which was given greater definition in the final version, are St. Thomas Aquinas and Pope Urbain IV, both of whom are associated in the panel’s program with the Feast of Corpus Christi.

[…]

Seated at the far right of the altar are two unidentified bishops, wearing gold mitres and robes, who may represent Early Christian defenders of “real presence”.

[…]

It has recently been proposed that the woman represents either the Archduchess Isabella, who together with her husband, Albert, governed the Spanish Netherlands from 1598 until her death in 1633 — or her patron, St. Clare (St. Claire of Assisi, the founder of the Poor Claires, or the Clarissens), who is usually shown holding a chalice or a monstrance. In several ways, these hypotheses would appear to be attractive. Certainly the archdukes, just as their Habsburg ancestors, revered all types of eucharistic devotion.” However, for Albert and Isabella, the veneration of the sacrament had diverse associations: by advancing a statecraft based on the premise of “one country, one faith,” they hoped to establish political unity in a nation beset by religious differences (expressed, most notably, by opposing attitudes towards the issue of “real presence”), in which the institution of the Church was to play a central role. Not only did Isabella later commission Rubens to design The Triumph of the Eucharist tapestry series, a subject related to the theme of the altarpiece in St.Paul’s, but also, again in her later years, she commissioned portraits of herself, both painted and engraved, in which she is depicted, by Rubens and others, as a nun, wearing the habit of the order of the Poor Clares.

Finally, as the patron of this order, St.Clare was also one of Isabella’s patron saints: she appears jn this role in the program for the ceiling of the Antwerp Jesuit Church, and as one of the defenders of the Eucharist in the Triumph of the Eucharist tapestry series, where she is presented with Isabella’s features.

However, when analyzed more critically, those hypotheses about the identity of the woman in the Real Presence become less credible. First, the woman is almost certainly not the Archduchess Isabella who adopted the habit of a tertiary of the Order of the Poor Clares only the death of her husband in 1621, some twelve years after the completion of the Real Presence. Second, it is also unlikely that the figure in Rubens’ panel is St. Clare who is most often depicted carrying a pyx or a monstrance containing the consecrated Host with which she fended off a band of Saracens who threatened her convent at Assisi there is no evidence of this attribute in Rubens’ painting. Furthermore, given St.Clare’s special significance for the Franciscans, one wonders why she would have been added to a work so dominated by Dominicans and those saints and holy figures the Dominicans revered, in a commission for a chapel in a Dominican church. For the same reasons, the inclusion of the archduchess, as a Franciscan tertiary, would also seem to be unlikely.

I believe that the key to the identity of the woman and her two male companions (who are not mentioned, let alone identified, in any of the earlier attempts to name the woman), is their physical proximity to Aquinas and Urban IV : I propose that all five figures are part of a coherent group, that was active in the origins of the Feast of Corpus Christi, in the diocese of Liege, during the thirteenth century. As noted elsewhere, the left-most seated figure is Aquinas (c. 1225-74), identified by his black and white Dominican habit as well as by the symbol of the sun on his chest, who appears in conversation with Urban IV (1261-64), seated adjacent to the altar, who is identified by his papal tiara and. cope with embroidered lapels. The primary rationale for the inclusion of these historical figures in Rubens’ fictive scene of the defense of Transubstantiation is their role in the invention of the celebration of Corpus Christi, a universal feast of the Church (celebrated on the Thursday following Trinity Sunday) which Urban IV had made official in the bull Transituris de hoc mundo (1264). In Rubens’ picture, the inclusion of Aquinas not only refers to the tradition that identifies him as the author of the text of the feast’s office and hymns,” but it also underscores the traditional association in the Low Countries of Corpus Christi with the Dominican Order. I believe that Aquinas was added to the picture only after it was determined that the Real Presence would be mounted above the altar which was the main site of the celebration of the Eucharist (prior to the completion of the high altar in 1639).

I propose that the female figure standing behind Aquinas and Urban IV, represents St.Juliana of Cornillon (1192-1258; also known as Juliana of Liege), who was of such significance in Antwerp around the time that the Real Presence was commissioned, that she was accorded an illustrated entry in Albertus Miraeus’ Sanctorum Galliae Belgicae imagines et elogia, quibus Religionis ortus progressusque in Belgio ostenditur (Antwerp, 1606), a compendium of indigenous saints and holy figures. Unfortunately there are apparently no portraits of Juliana, dating from her lifetime, with which Rubens’ woman can be compared.

Although the details of Juliana’s life differ from source to source,it is generally agreed that it was her vision(s) and her persistence that led to the initial celebration of the institution and gift of the Holy Eucharist in the diocese of Liège, and eventually to the elevation of this observance to a universal feast of the Church. As a child she and her younger sister Agnes had been brought to the convent at Cornillon following the death of her parents; there, under the guidance of Sister Sapientia, Juliana evidently learned sufficient Latin to become familiar with the writings of St. Augustine and St. Bernard.

After taking her vows in 1207, she devoted her days to menials tasks, such as working in the community’s dairy, and to prayer and contemplation. Her devotion to the Holy Eucharist was so strong that her superior built a chapel for her at the farm where she worked so that she could spend time in prayer. Two years later, at the age of sixteen, Juliana experienced her first vision: she saw the moon, radiating light with an indentation in its rim this image mystified Juliana as well as those to whom she described it. Two years later the meaning of this vision was made known to her by Christ himself: the moon was a symbol of the Church, while the indentation in its rim indicated that the Church was incomplete because it lacked a feast in honor of the Holy Sacrament. In spite of Juliana’s protests that this task should be given to a clergyman, she nonetheless set out to promote the feast. In this pursuit she found support in her devotion to the Holy Virgin, in whose honor she was said to have recited the Magnificat nine times daily.

Juliana was aided in her efforts to found the Feast of the Holy Sacrament by Eve of Liège (also known as Eve of St.Martin’s), a beguine who as Juliana’s closest confidante has often been identified as the source for the information contained in the Vita Juliane, the earliest and most authoritative of Juliana’s biographies. After Juliana’s death, it was Eve who rallied support for the Church’s acceptance of the feast: she is thought to have received preliminary copies of Transituris and of the feast’s office directly from Urban IV, together with a personal letter (whose contents and whereabouts are unknown). Through the intervention of a recluse at the Church of St. Martin, Juliana was brought to the attention of Jean of Cornillon (also known as Jean of Liege, or Jean of Lausanne), a canon of St.Martin’s who became her confessor: it was to him that she revealed her visions. It is tempting to consider that the hooded monk, with his back to the viewer, represents the nameless recluse, while the balding figure to the left of Juliana depicts Jean of Cornillon. Just as Aquinas, Jean is also credited with the text of an earl office for the Feast of Corpus Christi; however, his presence in the Real Presence depends on his having secured support for the initial celebration of the feast in the diocese from Jacques (or Jacob) Pantaleon, then Archdeacon of Liege, who was elevated to the papacy’ as Urban IV in August, 1261 — and who in this role appears beside Aquinas in Rubens’ picture. Thus, these five figures (Urban IV and Aquinas, together with Juliana of Liege, Jean of Cornillon and the monk) create a distinct subgroup within the larger council — one which I call the “Corpus Christi Cohort. “

Although the trio behind Aquinas and Urban IV js a relatively minor component in a densely populated work, the rationale for its inclusion in Rubens’ Real Presence has larger implications. First, that the identification of these figures appears to be based on their proximity to Aquinas and Urban IV suggests a potentially useful stratagem for identifying other “unnamed” figures in the Real Presence and in Rubens’ works more generally. Furthermore, figures like Juliana, Eve of St.Martin’s and Jean of Cornillon, who initiated and nurtured this and other eucharistic devotions, often in spite of strong persistent opposition, provided an inspiring model for later clergy facing similar challenges to “real presence” — for example in Antwerp at the time Rubens’ altarpiece wascommissioned. Also the inclusion of local figures within the Real Presence’s international council is consistent Post-Tridentine emphasis on the promotion of indigenous saints, martyrs and clergy, like those in Miraeus’ Sanctorum Galliae Belgicae, as evidence of the continuity of faith and practice. Finally, the “Corpus Christi Cohort,” whose members all originally hailed from the diocese of Liege, helped to underscore the long history of the devotion to the Eucharist in the Southern Netherlands, as well as the local origins of a devotion that was to become a universal feast of the Church.

RubensOnline:

Slechts twee van hen zijn herkenbaar: de H. Thomas van Aquino – links van het altaar, met een zon op de borst – en naast hem paus Urbanus IV die het feest van Corpus Christi instelde.

MANNAERTS Rudi, Sint-Paulus. De Antwerpse dominicanenkerk, Antwerpen, 2014: p. 78:

De paus, met de gouden tiara, is Urbanus IV (U), die door toedoen van de Luikse begijn, de heilige Juliana van Cornillon (♀), achter hem, in 1264 het feest van het Heilig Sacrament instelt: ‘Corpus Christi’. Hij is in een conversatie gewikkeld met de grote dominicaner theoloog Thomas van Aquino (T), die herkenbaar is aan de gouden kralenkrans ter hoogte van zijn borst.

- Twee figuren achter paus Urbanus IV

DONNET:

Achter het altaar staan links de H. Dominicus en Bonaventura.

- Twee bisschoppen rechts

- Ev, Ej en Ev: Evangelisten

VLIEGHE 1972 (Corpus Rubenianum):

In the right background are a number of young men in togas.

WUYTS 1992 (Kwintet):

Rechts achter het altaar staan drie jonge mannen in toga. Mogelijk zijn zij de evangelisten Lucas, Johannes en Mattheus, die in de evangelieboeken van de cherubijntjes geciteerd worden.

LAWRENCE 2000 (St.-Paulus-Info):

Directly across the altar are three figures which have been identified as Sts. Matthew, Luke and John; passages from their gospels referring to Transubstantiation are inscribed in the open books held by the putti in the panel’s upper register.

MANNAERTS Rudi, Sint-Paulus. De Antwerpse dominicanenkerk, Antwerpen, 2014: p. 78:

De baardloze jonge man in toga, gekleed in het rood, is Johannes de Evangelist. Zijn beide buren zijn vermoedelijk ook evangelisten.

- Geestelijken (3 achter Thomas van Aquino (één van hen met puntkap) en 3 aan de andere zijde van het altaar)

VLIEGHE 1972 (Corpus Rubenianum):

In the extreme background, on the left, five monks are seen in discussion; one wearing the Dominican habit, is pointing to the monstrance on the altar with a gesture of respectful devotion.

WUYTS 1992 (Kwintet):

De andere personages laten zich niet identificeren. Mogelijk was het ook niet de bedoeling ze als portretten voor te voeren.

LAWRENCE 2000 (St.-Paulus-Info):

Standing to the left of the altar are a Dominican and a Franciscan. thought by some to represent Sts. Dominic and Bonaventura: Rubens’ figures may simply allude to their respective orders’ devotion to the Eucharist or to their different positions on the nature of Eucharistic reception.

MANNAERTS Rudi, Sint-Paulus. De Antwerpse dominicanenkerk, Antwerpen, 2014: /

- Figuren zichtbaar op röntgenfoto’s

VLIEGHE 1972 (Corpus Rubenianum):

An X-ray photograph has shown that there were originally two more figures in the painting. To the left a young man looking up in ecstasy in the middle distance, a man’s face was to be seen frontally, and to the left of St. Gregory was the head, in profile, of a man reading. It is not clear why and by whom these heads were painted out; they had disappeared before 1643, as is shown by Snyers’ engraving of that year. In any case they must have formed part of Rubens’s original plan, as they figured in the oil sketch fort his altar-piece which is now lost but can be judged from two copies.

- Voorgrond: trap met boeken

De onderste strook bestaande uit een trap is toegevoegd door Gobau.

Zie: verdere geschiedenis. De twee gesloten boeken vertonen geen verdere identificatie van auteur of titel.

Aparte onderdelen van dit kunstwerk:

Predellapanelen:

ROOSES 1886-1892:

Dans les soubassements des colonnes de l’autel de cette époque se trouvaient les figures de Moïse et d’Aaron. Ces deux dernières ont fort probablement disparu en 1656, lorsque l’autel actuel fut construit.

VLIEGHE 1972 (Corpus Rubenianum):

Nrs. 57 en 58: p. 79-80.

WUYTS 1992 (Kwintet):

Nog spijtiger echter is dat daarbij de twee schilderstukken verloren gingen, die Rubens als een soort predella ter ondersteuning van de altaartafel had uitgevoerd. Ze stelden Mozes voor en Aäron.

MANNAERTS Rudi, Sint-Paulus. De Antwerpse dominicanenkerk, Antwerpen, 2014: p. 75:

Ca. 1609 bestellen de dominicanen bij Pieter Paul Rubens dit altaarstuk en de twee predellastukken Mozes en Aäron.

DONNET:

Bovendien verdwenen de twee predellastukken met voorstellingen van Mozes en Aäron, die oorspronkelijk onder het schilderij waren aangebracht. De keuze van de twee figuren is gebaseerd op Exodus 16:32-34: Mozes vraagt Aäron om het overschot aan manna, het brood dat uit de hemel viel, in het tabernakel te bewaren, wat geldt als voorafbeelding van de eucharistie.

MANNAERTS Rudi, De sleutel voor de openbaring van de Sint-Pauluskerk te Antwerpen, eertijds van de dominicanen, didactische syllabus, Toerisme Pastoraal, Antwerpen, 2011, p. 89-90:

Het hoofdtafereel werd ‘onderlijnd’ door twee predellastukken, nl. Mozes en Aäron, die echter in 1656 verdwenen bij de oprichting van het huidige barokke altaar. Het geestelijk voedsel van de communie wordt voorafgebeeld door het manna in de woestijn dat Mozes “uit de hemel liet regenen”(Exod. 16:4). Dit wonderlijke brood krijgt nog een explicietere eucharistische duiding doordat Mozes zijn oudere broer Aäron, die later (Ex. 28:1) tot priester aangeduid wordt, beval om een portie van het manna (bij de verbondsakte) in de verbondsark te bewaren (Exod. 16:32-34). Dit wordt dan opgevat als een voorafbeelding van de geconsacreerde hosties in het tabernakel, die bovendien enkel door een gewijde priester moge

n aangeraakt worden. Maar dat manna van Mozes hield – zo stelt Jezus – nog niet het échte heil in: “wat Mozes u gaf was niet het brood uit de hemel” (v. 32); uw vaderen, die het manna gegeten hebben in de woestijn, zijn niettemin gestorven” (v. 49). Deze woorden moeten Jezus’ toelichting benadrukken die hij uitsprak onmiddellijk na de wonderbare broodvermenigvuldiging (Joh. 6:1-15) wanneer hij het heeft over zichzelf als “het brood van het leven”(v. 35.48), “uit de hemel neergedaald”(v. 41.51) of door (God) de “Vader gegeven” (v.32) en dat leven aan de wereld geeft (v. 33), meer nog: het leven in eeuwigheid garandeert (v. 51).

Luiken ? (triptiek ?) Óf zonder luiken (: ensemble)?

1) Wanneer afgenomen ? / verkocht ? En verder?

2) Waarom niet ter plaatse bewaard gebleven?

Onderdeel van een groter geheel: /

Opdrachtgever:

VLIEGHE 1972 (Corpus Rubenianum):

Nothing is known of the circumstances in which it was commissioned. The rich merchant and connoisseur Cornelis Van der Geest may have helped to provide the money, as we know that in 1616 he advanced funds for the construction of a marble balustrade closing off the renovated chapel of the Holy Sacrament in the Dominican church (P. Rombouts and T. van Lerius, op. cit., 1, p. 461; I. Leyssens, Hans van Mildert, Gentsche Bijdragen tot de Kunstgeschiedenis, VII, 1941, pp. 100, 101).

BAUDOUIN Frans, Pietro Paolo Rubens, (Mercatorfonds) Antwerpen, 1977: p. 308:

Het wordt Van der Geest vooral als een bIijvende verdienste aangerekend, dat hij zeer vroeg Rubens’ meesterschap heeft erkend. Dank zij hem verkreeg de jonge kunstenaar in 1610 de opdracht tot het schilderen van het grote drieluik De Kruisoprichting voor het hoogaltaar van de Sint-Walburgiskerk, de parochiekerk van de mecenas (thans in de Kathedraal). Het is zelfs niet uitgesloten – maar bij gebrek aan documenten moeilijk te bewijzen – dat hij er een jaar tevoren reeds het zijne toe bijdroeg opdat Rubens voor de confrerie van de Zoete Naam Jezus in de Sint-Pauluskerk De Verheerlijking van de Heilige Eucharistie mocht schilderen, die thans nog op het altaar van dit broederschap prijkt. Dit is zeker niet onmogelijk, aangezien hij ook financieel blijkt tussengekomen te zijn in de kosten van de ‘marmeren tuin’ omheen dat altaar, die door de beeldhouwer Hans van Mildert werd vervaardigd. Hoe dan ook, hij heeft alleszins aan de jonge Rubens zijn vertrouwen geschonken op een ogenblik dat deze, pas terug uit Italië, nog de meesterwerken moest schilderen die zijn faam zouden vestigen.

Schenker:

BAUDOUIN Frans, Pietro Paolo Rubens, (Mercatorfonds) Antwerpen, 1977: p. 74:

Werd het schilderij door de Confrerie van het H. Sacrament uit gezamenlijke bijdragen van de leden bekostigd? Of werd het door een begunstiger aan de Broederschap geschonken? Blijkbaar zijn geen documenten bewaard gebleven die ons toelaten deze vragen te beantwoorden. Het is echter niet zonder belang er op te wijzen dat Cornelis van der Geest, die een groot bewonderaar van Rubens is geweest, in enge relatie moet hebben gestaan met de Broederschap. Dit betekent daarom nog niet dat hij het altaar zou hebben bekostigd. Maar het lijkt niet onmogelijk dat hij een zekere invloed heeft uitgeoefend bij de keuze van de schilder.

DONNET:

Het schilderij werd besteld door de Broederschap van de Zoete Naam Jezus voor haar altaar. Een van haar meest vooraanstaande leden was Cornelis van der Geest. Misschien speelde hij een rol bij het toekennen van de opdracht aan Rubens.

Voorstudies:

De reële aanwezigheid [van Christus] in het H. Sacrament: olieverfschets (modello)

(nr. 56a Corpus Rubenianum)

Olieverf op paneel; ca. 65 x 50 cm.

Verblijfplaats onbekend, waarschijnlijk verloren gegaan.

Herkomst: ? Cornelis van der Geest (Antwerpen, 1575-1638)

Kopieën van deze voorstudie:

- Tekening; toegeschreven aan J. de Bisschop volgens BURCHARD; bewaarplaats onbekend, ca. 730 x 480 mm., herkomst: Brussel, G. de Leval

- Tekening: bewaarplaats Albertina Wenen; nr. 15103, 363 x 265 mm.

Voorstudies voor predella:

- Mozes: nr. 57 Corpus Rubenianum: olieverf op paneel: verblijfplaats onbekend, waarschijnlijk verloren gegaan

Herkomst: Sint-Pauluskerk Antwerpen, 1616

- Aaron: nr. 58 Corpus Rubenianum: olieverf op paneel: verblijfplaats onbekend, waarschijnlijk verloren gegaan

- Herkomst: Sint-Pauluskerk Antwerpen, 1616

Herkomst: /

Verdere geschiedenis:

- Vergroting

1) Wanneer ? En 2) door wie ?

3) Waar en 4) hoe groot vergroot?

5) effect qua compositie ? En 6) qua iconografie?

ROOSES 1886-1892:

Le panneau est été agrandi, d’un tiers environ, en hauteur; des pièces ont été ajoutées en bas et en haut; les planches se sont disjointes et le temps a affaibli la vigueur du coloris.

- 1654-1658 / 1680:

VLIEGHE 1972 (Corpus Rubenianum):

Closer inspection shows that the picture was enlarged on all four sides, with strips of about 8 cm. on the left and right, 34 cm. at the top and 67 cm. at the bottom. This indicates that it was first of all reduced in size, presumably on account of damage at the edges, and afterwards enlarged as required. The circumstances that led to these enlargements have not previously been noted. In 1654 the sculptor Pieter Verbruggen the Elder contracted to make a completely new altar of the Holy Sacrament “van de grootte ende materialen conforme den aultaer van Onze Lieve Vrouwe” (“of like size and materials to Our Lady’s altar; A. Jansen, Het O.L. Vrouwaltaar in de St. Paulus kerk te Antwerpen, Tijdschrift voor Geschiedenis en Folklore, IV, 1941, p. 138) – i.e. the altar of Our Lady of the Rosary erected in 1650 on the opposite side of the church, in the north transept (A. Jansen, op. cit., pp. 139-145). The words quoted suggest that the intention was for the side-altars to be wholly symmetrical. Verbruggen’s altar, like that of the Rosary chapel, is still extant. The date 1658 appears in a cartouche at the top (illustrations of both altars in Jansen, op. cit., pis. 1 and 2), and this is evidently the year in which it was completed. Rubens’s panel is of approximately the same dimensions as Caravaggio’s Madonna of the Rosary (oil on panel, 364 : 249 cm., now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum at Vienna, cat. No. 483; W. Friedländer, Caravaggio Studies, Princeton, 1955, pl. 39), which adorned the altar in the north transept from c. 1620 to the end of the eighteenth century. It may thus be assumed that during the reconstruction of 1654-58 the dimensions of Rubens’s work were enlarged to correspond to those of the Caravaggio.

An entry in the accounts of the Sodality of the Sweet Name of Jesus suggests that the enlargement took place during the reconstruction of the altar: the sum of 60 guilders was paid in 1657 to Antoon Goubau (1616-1698) “voor de schilderij van den vollen Aflaet” (“for the painting of the Plenary Indulgence” ), which can scarcely refer to any other picture than the one now in question (P. Rombouts and T. van Lerius, op. cit., 11, p. 3). There is, however, an apparent contradiction here with items of 1680: “Aen den schrynwercker, voor het vergrooten van de schilderye van den autaer van het Alderheylichste Sacrament, fl. 50. Voor het pourmueren van de schildereye, fl. 8. Voor de lijste van de schilderye van het Alderheylichste Sacrament, ende van de zelve te vergulden, fl. 14. Monsieur Goubau, den schilder getracteert voor het vergrooten van de schilderye van den autaer, par courtoisie, fl. 12.” (“To the joiner, for enlargement of the painting on the altar of the Most Holy Sacrament, 50 guilders; for the priming thereof, 8 guilders; for the frame of the painting of the Most Holy Sacrament, and for gilding the same, 14 guilders. To Monsieur Goubau, the painter commissioned to enlarge the altar-piece, par courtoisie, 12 guilders”; P. Rombouts and T. van Lerius, op. cit., p. 3, n. 2). Perhaps the explanation is that when the retable was rebuilt in 1654-58 Goubau carried out some superficial restoration of the painting, which was too small for its new setting, but that, perhaps owing to shortage of funds, it was not finally adapted to the new dimensions until 1680.

WUYTS 1992 (Kwintet):

Deze nieuwe architecturale omlijsting vergde evenwel een aanpassing van het altaarstuk dat aan de boven- en onderkant met een brede strook vergroot werd. Helaas werd daardoor de evenwichtigheid van de compositie enigszins verstoord.

MANNAERTS, Syllabus, 2012:

De brede trap met daarop twee boeken is eveneens geïnspireerd door Raphael’s Disputa. Hoe geslaagd ook als realisme de toevoeging doet afbreuk aan de oorspronkelijke Rubensiaanse dynamiek.

MANNAERTS Rudi, Sint-Paulus. De Antwerpse dominicanenkerk, Antwerpen, 2014: p. 75:

Om netjes in dit portiekaltaar te passen wordt Rubens’ paneel in 1680 vergroot, vooral onder- en bovenaan, maar ook een weinig in de breedte (tot 377 x 246 cm).

http://www.rubensonline.be/showDetail.asp?artworkID=100490:

In de jaren 1654-58 werd het oorspronkelijke uitzicht van het altaar grondig gewijzigd. Het grote paneel werd daarbij van formaat gewijzigd. Bovendien verdwenen toen waarschijnlijk de twee predellastukken die oorspronkelijk onder het schilderij waren aangebracht: een ‘Mozes’ en een ‘Aaron’.

DONNET:

In de jaren 1654-58 werd het oorspronkelijke uitzicht van het altaar grondig gewijzigd toen Peter I Verbruggen een nieuw Venerabelaltaar bouwde naar het voorbeeld van het Rozenkransaltaar. Het grote paneel veranderde daarbij van formaat. Bovendien verdwenen de twee predellastukken met voorstellingen van Mozes en Aäron, die oorspronkelijk onder het schilderij waren aangebracht.

- Opeising als oorlogsbuit door de Fransen in 1794 – terugkeer ter plaatse in 1816

- 1794: Na de herovering van Antwerpen op de Oostenrijkers in 1794 eist de Franse bezetter oorlogsbuit: niet alleen geldelijk, maar ook in natura. Omwille van de roem van de kunstenaar wordt dit schilderij samen met de andere werken van Rubens, Jordaens en van Van Dyck in deze kerk in dat jaar als oorlogsbuit in beslag genomen en meegenomen naar het Musée Central des Arts te Parijs (gevestigd in het Louvre-paleis).

- December 1815: Na de nederlaag van Napoleon keert het naar Antwerpen terug in december 1815. Na expositie in het lokale museum in 1816 wordt het teruggeplaatst op zijn oorspronkelijke bestemming in de Sint-Pauluskerk.

PIOT 1883:

No d’ordre: 44; Provenance: église des dominicains, dite aujourd’hui de Saint-Paul; sujet et auteurs: Le mystère de la transubstantion, ou Concile sur l’Eucharistie; par Rubens; date de l’enlèvement: 1794’.

ROOSES 1886-1892:

Enlevé par les commissaires de la République française en 1794, il fut restitué en 1815.

VLIEGHE H., Het verslag over de toestand van de in 1815 uit Frankrijk naar Antwerpen teruggekeerde schilderijen in Jaarboek KMSKA, 1971: p. 280:

Doc. 3: ‘Séance du 18 decembre 1815. Proces-verbal de la Commission pour le Déballage et la reception des tableaux récuperés sur la France et appartenants a la ville d’Anvers’: ‘Un tableau sur bois de Rubens ou Sallaert, provenant de l’église des dominicains et répresentant un Concile sur la Sainte Eucharistie, Mrs les Delegués ont déclaré d’avoir récupéré ce tableau dans un très mauvais état, les planches du panneau etaient presque toutes detachées, Messieurs les commissaires pour la réception ont remarqué ensuite une legère blessure au milieu du tableau et plusieurs taches de chanci sur la partie inférieure dans les marches.’

Restauraties:

1968: omwille van de brand uit de lijst genomen

1969-70: het paneel wordt hersteld door de zorgen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor het Kunstpatrimonium te Brussel (bron: JANSSENS, 1971: p. 80).

2000: geconserveerd dankzij het mecenaat van dr. en mevrouw Herman Geuens (bron: SIRJACOBS, 2001: p. 72).

Tentoonstellingen:

Tableux recouvrés … revenus de France, Musée, Antwerpen, 1816: nr. 33 (als een A. Sallaert).

God en de goden, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, Amsterdam , 1981-05-16 – 1981-07-19, nr. 6.

Tentoonstellingen na 1972

- A) Andere kunstwerken die dit kunstwerk hebben beïnvloed:

- Dit kunstwerk is geïnspireerd door:

- Dit kunstwerk is gekopieerd naar: /

- B) De invloed van dit kunstwerk op andere kunstwerken:

- Dit kunstwerk is in prent omgezet (door):

– Gravure: Hendrik Snyers (prentmaker), 1643, Abraham van Diepenbeeck (uitgever)

- Rijksmuseum:

- http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.337848

- Dit kunstwerk is inspirerend voor:

Abraham Bloemaert, De vier kerkvaders vereren de eucharistie, ca. 1629, pen in bruin, bruin gewassen, 47 x 34,5 cm, particuliere collectie, New York

- Dit kunstwerk is gekopieerd (door):

Kopieën:

(1) Tekening naar de rechterzijde, verblijfplaats onbekend; 355 x 280 mm.

(2) Tekening naar de hoofden van de vermoedelijke heiligen Ambrosius, Augustinus en Paulus, aan de linkerzijde, verblijfplaats onbekend; 146 x 159 mm.

(3) Gravure door Hendrik Snyers (prentmaker) Abraham van Diepenbeeck (uitgever), 1643

- Meer informatie: Rijksmuseum:

http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.337848

ROOSES 1886-1892:

V.S. 28, Henr. Snijers (Dédicace: Adm. Rdo Pri Fri Christophoro Meichsner Prædicatori gnali a P.P. ord. Prædicatorum Antverpiæ Priori. Anno 1643.)

Dans la gravure de Snijers, on ne voit qu’un des deux degrés conduisant â l’estrade où siègent les docteurs et les deux livres tombés à terre sont omis. La gravure montre, dans le haut, les chapiteaux des colonnes qu’on ne distingue pas dans le tableau. Le n°29 de V.S. ne représente pas le même sujet, comme le dit cet auteur. Cette planche, la même que son n° 9, fugure les Quatre Évangelistes et les Docteurs de l’église du Triomphe de l’Eucharistie.

Voorhelm Schneevoogt mentionne sous le n° 30 le même sujet représenté par quatre pères de l’église et St. Thomas au milieu d’eux, gravé par un anonyme, sans nom de peintre. Il appelle la pièce douteuse; en effet elle ne saurait être attribuée à Rubens.

Le catalogue de la galerie du Seigneur de Brabek à Hildesheim (Hanovre, 1792) mentionne sous le n°53 “une belle esquisse de Rubens: Dispute sur le Saint Sacrement, grisaille, H. 1 pied 10 ¾ pouces, L. 1 pied 5 pouces. Un bijou pour le connaisseur, les têtes sont pleines de caractère, les vêtements des étoffes véritables, toutes les figures bien disposées et heureusement éclairées”.

Parthey signale une composition traitant le même sujet dans la collection Majer de Stuttgart.

VLIEGHE 1972 (Corpus Rubenianum):

Other interesting points may be noted in connection with Hendrik Snyers’s engraving of 1643. On 3 September 1642 Snyers entered the service of Abraham van Diepenbeeck, who shortly afterwards secured a twelve-year privilege on the Strength of a declaration that he had “for some years” been making drawings of “rare and ingenious pictures” and now wished to make engravings from them (F.J. Van den Branden, Geschiedenis der Antwerpsche Schilderschool, Antwerp, 1883, p. 784). Abraham van Diepenbeeck’s daughter Anna Theresa made a will of 5 December 1701, which refers inter alia to “some copperplates after Rubens… secondly: the Disputation of the Holy Sacrament, of the Dominican Fathers” (F.J. Van den Branden, ibid.). It is probably to be inferred from this that Snyers’s engraving was actually made from a drawing by Van Diepenbeeck.

(4) Schilderij door Simon de Vos naar Peter Paul Rubens, Het dispuut der kerkvaders over het heilige sacrament, olieverf op koper, ovaal, 41x 31 cm.

- Meer informatie: https://rkd.nl/nl/explore/images/252279

(5) Karton voor wandtapijt naar Pieter Paul Rubens, Het dispuut der kerkvaders over het heilige sacrament, na 1610, bestemd voor Valletta (Malta), St. John’s Co-Cathedral, abdijkerk Grimbergen Sint-Norbertuskapel alias Sacramentskapel

(6) Wandtapijt naar Pieter Paul Rubens, Het dispuut der kerkvaders over het heilige sacrament, na 1610, Valletta (Malta), St. John’s Co-Cathedral

- Meer informatie: https://rkd.nl/nl/explore/images/252281

(7) Tekening naar Pieter Paul Rubens, Het dispuut der kerkvaders over het heilige sacrament, na 1610, Brussel, Koninklijke Musea voor Schone Kunsten van België, inv./cat.nr 10 244.

- Meer informatie: https://rkd.nl/nl/explore/images/252286

(8) Schilderij Abraham van Diepenbeeck naar Peter Paul Rubens, Het dispuut der kerkvaders over het Heilig Sacrament, olieverf op paneel, 59,3 x 44,5 cm., Karlsruhe, Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe.

Datering van dit schilderij in Karlsruhe:

– Volgens online catalogus van Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlruhe: inv. nr. 2836, datering 1654-1658; https://www.kunsthalle-karlsruhe.de/kunstwerke/Abraham-van-Diepenbeeck/Die-Disputation-%C3%BCber-die-Gegenwart-Christi-in-der-Eucharistie/2B6BAD8E418E6CA41CC501AB503D6F5D/

– Volgens RKD is ‘ca. 1609 (1608-1610)’: https://rkd.nl/nl/explore/images/29256

Meer informatie over de kopieën: VLIEGHE Hans, Corpus Rubenianum, dl. 8, Saints, dl. 1, Brussel 1972: p. 73-80. Of: http://www.rubenianum.be/nl/pagina/corpus-rubenianum-ludwig-burchard-online

OPGELET: indien u een andere taal gekozen hebt, zullen de titels van deze boeken en artikels helaas automatisch mee vertaald worden!

U kan zelf de bibliografie sorteren op jaartal of op auteur.

@Jaar | @Auteur | Referentie |

1757 | [BERBIE G.] | Description des principaux ouvrages de peinture et sculpture, acluellement existans dans les églises, couvens & lieux publics de la ville d’Anvers, 3rd ed., Antwerpen, 1757: p. 61, nr. 9. |

1672 | BELLORI G.P. | Le Vite de’ pittori, scultori ed architetti moderni, Rome, 1672: p. 223. |

1765 | BERBIE Gerardus | Beschryvinge der bezonderste werken van de schilder-konste ende beeldhouwerye, nu tr tyd zynde in de kerken, kloosters, ende openbaere plaetsen der stad Antwerpen, in het licht gegeêven tot profijt der Reyzers. Op nieuws overzien, verbetert ende vermeerdert, Antwerpen, 1765: p. 75-76. |

1666 | DE MONCONYS M. | Journal des Voyages, II, Lyon, 1666: p. 107 (ad 1663). |

1910 | DE WIT Jacobus, DE BOSSCHERE J. | De kerken van Antwerpen. Schilderijen, beeldhouwwerken, geschilderde glasramen, enz., in de XVIIIe eeuw beschreven door Jacobus de Wit. Met aantekeningen door J. De Bosschere en grondplannen, Antwerpen, 1910: p. 57. |

1753 | DESCAMPS J.B. | La vie des peintres flamands, allemands et hollandais, I , Parijs, 1753: p. 322. |

1769 | DESCAMPS Jean Baptiste | Voyage pittoresque de la Flandre et du Brabant avec des réflexions relativement aux arts & quelques gravures, Parijs, 1769: p. 190-191. |

1909 | DILLON E. | Rubens, Londen, 1909: p. 98, 105, 211. |

1942 | EVERS H.G. | Peter Paul Rubens, München, 1942: p. 60, 61, repr. |

1971 | JANSSENS Aloïs | Sint-Pauluskerk te Antwerpen en haar kunstbezit, Antwerpen, 1971: p. 80. |

1939 | KNIPPING B. | De iconografie van de Contra-Reformatie in de Nederlanden, dl. II, Hilversum, 1939-1940: p. 86, 87. |

2000 | LAWRENCE Cynthia | Notes on the iconography of Rubens’ Real presence in the Holy Sacrament: the Corpus Christi Cohort in Sint-Paulus-Info, nr. 68, 2000: p. 1562-1569. |

2014 | MANNAERTS Rudi | Sint-Paulus. De Antwerpse dominicanenkerk, Antwerpen, 2014: p. 75-78. |

1763 | MENSAERT G.P. | |

1771 | MICHEL J.F.M. | Histoire de la vie de P.P. Rubens, Brussel, 1771: p. 88. |

1922 | OLDENBOURG R. | Peter Paul Rubens, uitgegeven door W. von Bode, München-Berlijn, 1922: p. 61, 73. |

1921 |

| P.P. Rubens, Des Meisters Gemälde, ed. by R. Oldenbourg, Klassiker der Kunst, v, 4de ed., Stuttgart-Berlijn, [1921]: p. 28. |

z.d. | ROMBOUTS T. en VAN LERIUS P. | De Liggeren en andere historische archieven betreffende het Antwerpsche Sint-Lucasgilde, I, Antwerpen, z.d.: p. 402, nr. I; II, Den Haag, z.d.: p. 3, nr. 2. |

1886 | ROOSES M. | L’Œuvre de P.P. Rubens, histoire et description de ses tableaux et dessins, dl. II, Antwerpen, 1886-1892: p. 196-199, nr. 376. |

2001 | SIRJACOBS Raymond | Sint-Pauluskerk Antwerpen. Historische gids, 2de herw. uitg., Boechout, 2001: p. 70-73. |

1829 | SMITH J. | A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch, Flemish and French Painters, dl. II, Londen, 1829- 1842: p. 11. |

1914 | TESSIN N. | Studieresor i Danmark, Tyskland, Holland, Frankrike och Italien, ed. by O. Sirén, Stockholm, 1914: p. 83. |

1972 | VLIEGHE Hans | Corpus Rubenianum, dl. 8, Saints, dl. 1, Brussel 1972: p. 73-80, afb. 100-103. |

1992 | WUYTS Leo | De ‘disputa’ van P.P. Rubens. St-Pauluskerk in Kwintet. Nieuwsblad van de vijf monumentale kerken van Antwerpen, nr. 9, 1992: p. 63-65. |

* Iconografie personages/ter vergelijking

DUERLOO Luc, THOMAS Werner, THOMAS W. e.a., Albrecht & Isabella 1598-1621: tentoonstelling, tent. cat., Brussel, 1998: p. 284 (cat. nr. 392).

* Gravures naar P.P. Rubens:

Prent uitgevoerd door H. Snyers, naar ontwerp van P.P. Rubens

DE MAERE J. en WABBES M., Illustrated dictionary of 17th century Flemish painters, Brussel, 1994: p. 345. (afbeelding van de gravure door Abraham van Diepenbeeck in Karlsruhe)

* Verdere geschiedenis:

@Jaar | @Auteur | Referentie |

1883 | [ODEVAERE J.] | Liste générale des tableaux et objets d’art arrivés de Paris, ..., in C. Piot, Rapport à Mr le Ministre de l’Intérieur sur les tableaux enlevés à la Belgique en 1794 et restitués en 1815, Brussel, 1883: p. 317, nr. 44 (“par Rubens ou Sallaert”). |

1962 | VAN DEN NIEUWENHUIZEN J. | Antwerpse schilderijen te Parijs (1794-1815), Antwerpen, VIII, 1962: p. 79. |

1971 | VLIEGHE H. | Het verslag over de toestand van de in 1815 uit Frankrijk naar Antwerpen teruggekeerde schilderijen in Jaarboek KMSKA, 1971: p. 280. |

*Literatuur voorstudie:

@Jaar | @Auteur | Referentie |

1926 | BURCHARD, L. | Skizzen des jungen Rubens, Sitzungsberichte der kunstgeschichtlichen Gesellschaft Berlin, oktober 1926- mei 1927: p. 2. |

1933 | BURCHARD, L. | Nachträge in Glück, 1933: p. 382. |

1947 | BURCHARD, L. | in Cat. Exh. Some pictures from Dulwich Gallery, National Gallery, Londen, 1947, onder nr. 45. |

1972 | VLIEGHE Hans | Corpus Rubenianum, dl. 8, Saints, dl. 1, Brussel 1972: nr. 56a: p. 78-79. |

*Literatuur predella:

ROMBOUTS T. en VAN LERIUS P., De Liggeren en andere historische archieven betreffende het Antwerpsche Sint-Lucasgilde, I, Antwerpen, z.d.: p. 402.

ROOSES M., L ’Œuvre de P.P. Rubens, histoire et description de ses tableaux et dessins, dl. I, Antwerpen, 1886-1892: p. 138, nr. 110-111.