Het vierde Droeve Mysterie

De Kruisdraging

Type kunstwerk: schilderij

Antoon Van Dyck anders bekeken – over ‘registers en contrefeytsels, tronies en copyen’ in Antwerpse kerken en kloosters, (ttst.cat.), Antwerpen, 1999 (uitg. TOPA):

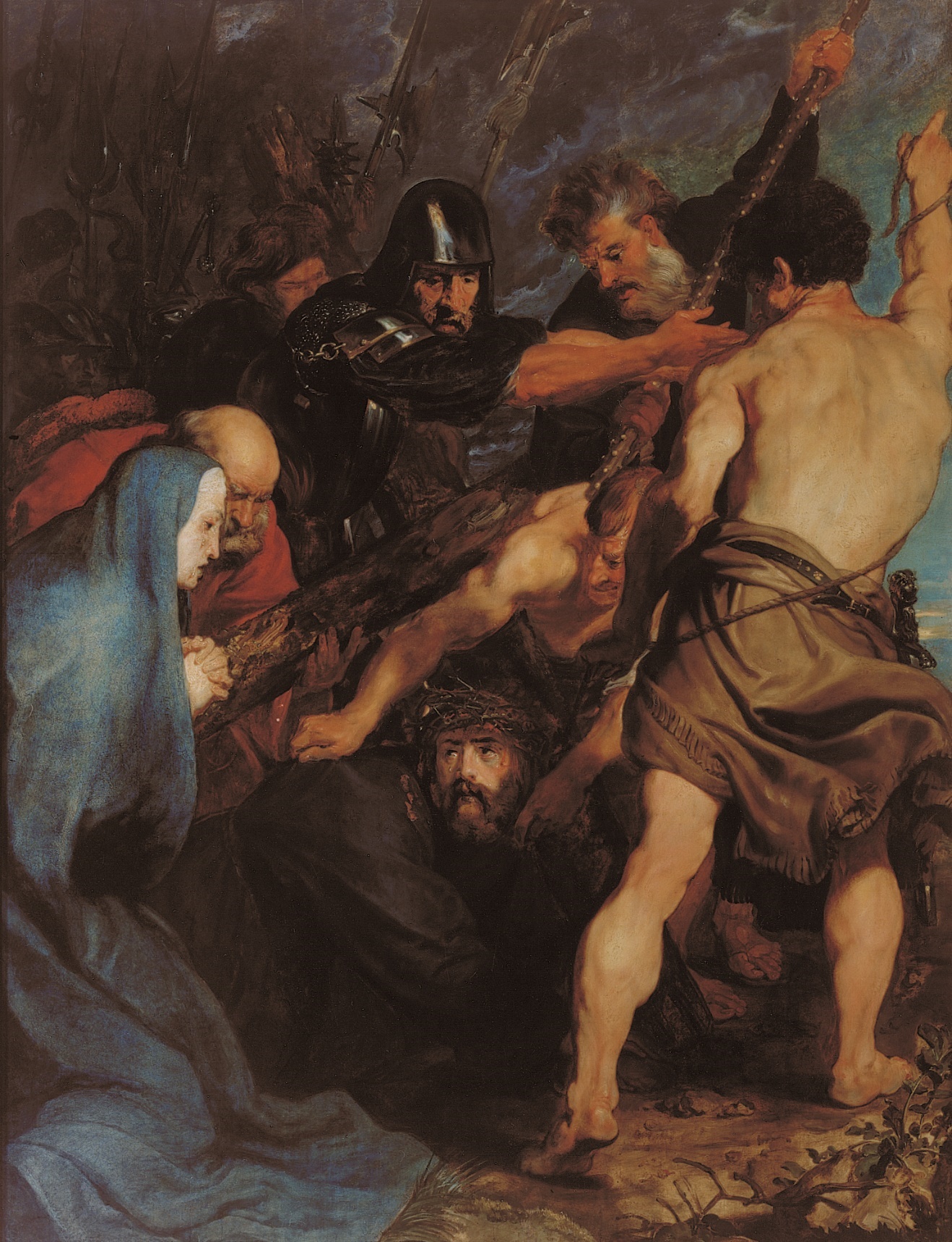

Omtrent de iconografie van dit schilderij bestaat ook enige verwarring. Het gaat hier wel degelijk om de kruisdraging van Christus, één van de vijf droevige mysteries van het rozenkransgebed. Maar in één enkel tafereel heeft Van Dyck verschillende elementen samengebracht, zoals de val onder het kruis die zich tot drie maal toe herhaalde, de hulp van Simon van Cyrene, en de ontmoeting van Christus met Zijn moeder Maria, wegens de bijzondere devotie die de broederschap voor de Moeder Gods koesterde.

De broederschap van de Rozenkrans werd door de Antwerpse dominicanen opgericht ter gelegenheid van de zeeslag van Lepanto, waarbij de katholieke vloot op 7 oktober 1571 de zege behaalde op de Turken. Deze overwinning was te danken aan het bidden van het rozenkransgebed, een initiatief van de dominicanerpaus Pius V. Dit verklaart waarom de dominicanen een bijzondere voorliefde vertonen voor de Rozenkrans, die ook in het Antwerpse dominicanenklooster alom uitgebeeld werd: op schilderijen, beelden, reliëfs, en vooral op de lambriseringen van de biechtstoelen. De broederschap bestaat nog steeds, en schonk door de eeuwen heen meerdere kunstwerken aan de St.-Pauluskerk, onder meer vier doeken over de slag van Lepanto door Jan Peeters in 1671, en vier glasramen door Marc de Groot in 1971.

MANNAERTS 2014: p. 113-115:

Dit is één van de vroegste werken van Van Dyck: hij was toen nog geen twintig jaar.

[…]

Verschillende taferelen van Jezus’ kruisweg zijn hier tot één voorstelling samengevoegd. Jezus valt onder het kruis. Beulsknechten en een soldaat dwingen Jezus op te staan en verder te gaan. Ze trekken aan het touw om Zijn middel, porren Hem met een essenhouten stok aan en helpen de dwarsbalk van het kruis op te heffen. De ontmoeting met zijn moeder Maria. Maria’s gelaat, in profiel, is gehuld in een intens blauwe mantel – met lapis lazuli als pigment. De emotie van haar moederhart is af te lezen aan haar gespannen blik en de tranen, terwijl ze door de knieën gaat. Jezus’ blik zonder woorden, achterom opkijkend naar zijn geknielde moeder, zegt genoeg. Ten derde is er de hulp die de opgevorderde Simon van Cyrene, in opvallende helrode kledij achter Maria, aanbiedt door het kruis mee te dragen.

De lansen en hellebaarden, die opgaan in de duistere lucht van de achtergrond, versterken het contrast tussen het machtsvertoon van de gezaghebbers en het onmenselijke verdriet van ‘moeder en kind’.

DONNET:

Negende schilderij in de reeks van de Vijftien Mysteries van de Rozenkrans, het vierde der Droeve Mysteries: De Kruisdraging van Christus. Van Dyck vat verschillende staties van Jezus’ lijdensweg samen in één voorstelling. De focus ligt op de ontmoeting tussen de gevallen Heiland en Zijn moeder. Christus bezwijkt onder de last van het kruis en kijkt naar zijn wenende moeder die naast de weg staat, en door de knieën gaat. De mantel van Maria is geschilderd met ultramarijn (lapis lazuli): het intens blauw vestigt de aandacht op Maria, die in deze schilderijencyclus vereerd wordt. Jezus kijkt achterom naar haar op. Achter Maria staat een kale man met baard, in het rood gehuld: Simon de Cyrener, die helpt Jezus het kruis terug op te nemen, door de basis ervan op te tillen. Drie beulsknechten (één met blote rug naar ons gekeerd, uiterst rechts, een touw windt zich om zijn middel en rechterarm die hij hoog heft; één, ook met ontbloot bovenlijf, trekt met beide handen aan Christus’ schouders, een derde, met grijze baard en donker gekleed, stoot met beide handen een lange en gedraaide essenhouten stok richting Jezus) én een soldaat met helm en harnas, die mee kracht zet op de stok, dwingen Christus terug op te staan en verder te gaan: ze trekken aan het touw om Zijn middel, porren Hem met de stok aan en helpen de dwarsbalk van het kruis op te heffen. De optocht trekt van links naar rechts. Op de achtergrond zien we de pieken en lansen van de begeleidende ordedienst, die zich aftekenen tegen een donkere, bewolkte lucht. Aan de horizon (midden rechts) zien we het licht van de ondergaande zon.

Aparte onderdelen van dit kunstwerk: /

Onderdeel van een groter geheel: Rozenkransreeks

Opdrachtgever:

Schenker:

ROOSES 1906; JANSSENS 1971:

Volgens de lijst in het archief van de Sint-Pauluskerk (overgenomen door ROOSES, 1906: p. 10-11): Jan van den Broek († 1649, kapelheer van de rozenkransbroederschap sinds 1611 en tevens stadsaamoezenier), 150 gulden.

JANSSENS 1971; SIRJACOBS 2001:

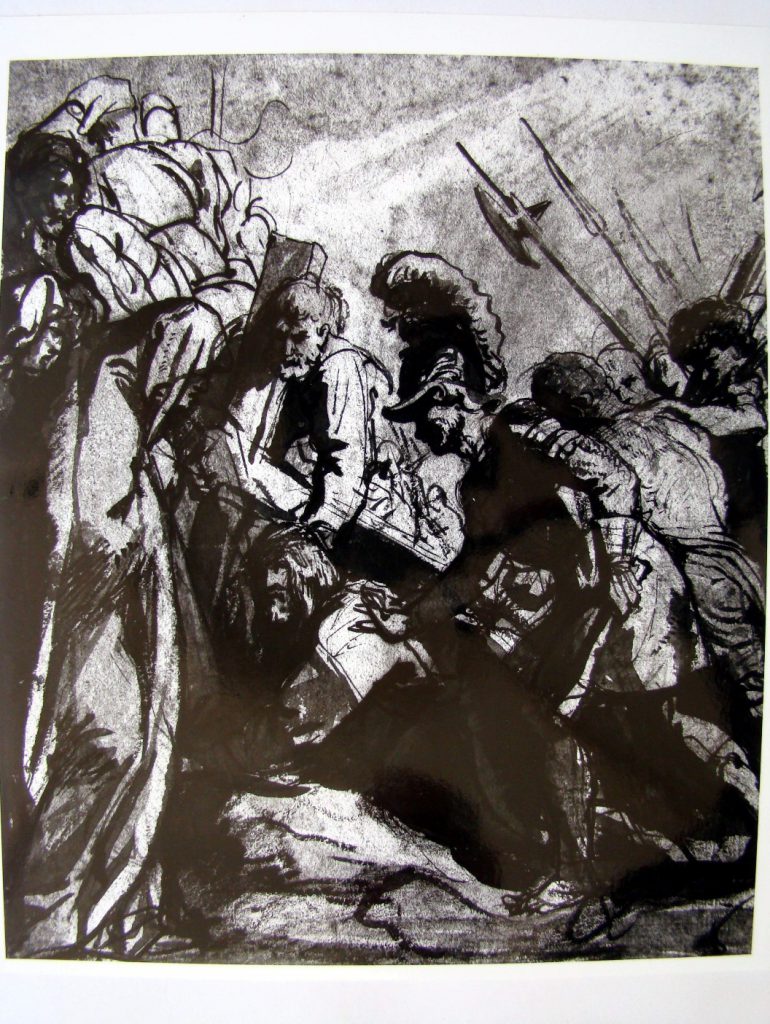

Negen van die tekeningen zijn compositiestudies. De andere is een studie in zwart krijt voor een voorovergebogen man die de armen uitstrekt om Christus mee te trekken aan zijn gewaad, gemaakt naar een model in het atelier.

De nog jonge Van Dyck (18 à 19 jaar) bereidde zich grondig voor: er zijn niet minder dan vele ontwerptekeningen bekend, die bewaard worden in Antwerpen (Museum Plantin-Moretus), Berlijn, Turijn (Biblioteca Reale), Lille (Palais des Beaux Arts), Chatsworth (The Trustees of the Chatsworth Settlement), Vorden, Bremen, Londen en Rhode Island (School of Design, Museum of Art, Providence).

Antoon Van Dyck anders bekeken – over ‘registers en contrefeytsels, tronies en copyen’ in Antwerpse kerken en kloosters, (ttst.cat.), Antwerpen, 1999 (uitg. TOPA): p. 63-66:

Opmerkelijk is niet dat Rubens en Jordaens hiervoor elk 150 gulden kregen, maar wel dat de 18-jarige Antoon Van Dyck dezelfde som toebedeeld kreeg. Alleen Hendrik van Balen kreeg meer, namelijk 216 gulden; alle anderen werden minder betaald.

Zo werd Antoon Van Dyck betaald door Jan van den Broek († 1649), kapelheer van de Rozenkransbroederschap sinds 1611 en tevens stadsaalmoezenier.

VERGARA Alejandro en LAMMERTSE Friso, The young Van Dyck, Londen, 2013: p. 149:

This painting is one of the few commissions from the young Van Dyck for which there is documentary evidence. It was painted for the church of of the Dominicans of Antwerp; the artist earned 150 florins for his work, paid to him by Jan van den Broeck, almoner of Antwerp and kapelmeester of the Brotherhood of the Rosary. (Recorded in a church fabric document, dated 1651 but copied from original documentation (ROOSES 1906, p. 11-12.)

Voorstudies:

Antoon Van Dyck anders bekeken – over ‘registers en contrefeytsels, tronies en copyen’ in Antwerpse kerken en kloosters, (ttst.cat.), Antwerpen, 1999 (uitg. TOPA): p. 63-66:

Dat deze Kruisdraging één van de vroegste werken van Van Dyck is, en dat hiervan niet minder dan tien ontwerptekeningen bewaard bleven, maakt van dit schilderij een uitzonderlijk document voor de studie van de jonge meester. …

Voor geen enkel schilderij van Antoon Van Dyck bestaan zo veel ontwerptekeningen als voor De kruisdraging. Indien er na vierhonderd jaar nog tien schetsen bewaard zijn, kan dit alleen maar duiden op het belang van deze opdracht voor de jonge schilder. Via negen schetsen – het waren er ongetwijfeld wel meer – evolueert de compositie van horizontaal naar verticaal, van een beweging naar links tot een beweging naar rechts. De tekening in het Prentenkabinet te Antwerpen (cat. 28k) wordt aangezien als het eigenlijke modello wegens de aanwezigheid van een rasterpatroon.

Toch werden in het schilderij zelf nog een paar aanpassingen doorgevoerd. Terwijl Antoon Van Dyck aan het schilderen was, liet hij in zijn atelier figuren poseren om bepaalde houdingen nader te bestuderen. Eén ervan is bewaard gebleven, namelijk een studie voor de beul die aan Jezus kleed trekt (cat. 28j). Het is, beginnende van links, de tweede arm die ten slotte weerhouden werd.

VERGARA Alejandro en LAMMERTSE Friso, The young Van Dyck, Londen, 2013: p. 139-148:

It is evident that Van Dyck struggled in creating Christ carrying the Cross, because there are more preparatory drawings known today with one detailled study of a man’s right arm and two indistinct, fragmentary versos. … The proper sequence of the numurous preliminary drawings rendering the procession to Calvary is not easy to establish. The order Horst Vey suggested for Christ carrying the Cross in his exemplary 1962 catalogue of Van Dyck drawings is still widely accepted but is here somewhat modified, especially in the beginning. According to VEY, Van Dyck began with the highly finished compositional drawing in Providence, Rhode Island, that is already in the upright format of the painting. The figures are moving towards the left where the Virgin is standing close tot Christ, who has fallen under the weight of the cross, and gazes up at her. Simon of Cyrene helps him to carry the cross. A roman soldier with a plumed helmet touches Christ on the shoulder, urging him along. The multiple changes and corrections in the drawing, added in various media drawn on top of each other, reflect Van Dyck’s intense struggle to find a solution. Some of the was hand certainly the blue chalk are later additions, while the black chalk appears tot be part of the original.

Finally the action happens in the wrong direction, i.e. from right to left compared with the rest of the Mysteries of the Rosary cycle, which progresses from left to right. Its composition also differs noticeably from the final painting in Saint Paul’s.

To begin with, in my opinion it is highly unlikely that such a large, well-defined drawing was the first design, especially since Van Dyck’s preliminary work for Christ carrying the Cross proved to be so extensive and laborious. Rather, he probably began with the smaller, less developed and more exploratory studies on a horizontal format, such as the quick sketches in Turin (recto and verso), to lay out the principal figures, drawn mostly with the brush. Also dating from the beginning must be the rather indistinct chalk rendering of Christ fallen under the weight of the cross on the verso The betrayal of Christ study in Berlin. Its composition is closer to the large drawing in Providence, where the Virgin is now standing near the top of the cross instead of near the bottom, as on the verso in the Berlin drawing. The highly finished Christ carrying the cross drawing in Providence would follow here, in my opinion, rather than having been made first. At this point, Van Dyck abandoned his initial design and began a new after having decided to fall in step with the rest of the Mysteries of the Rosary cycle and change direction.

This happens first in another quick scribble on the verso of the Turin sheet where Christ is moving with the cross towards the right. It is remarkable that Van Dyck would decide these basic changes in such minimal notations, obviously meant only for himself since the would have made little sense to anyone else.These scribbles, quick reminders to himself, make us realise that Van Dyck must have had many of his prelimanary drawings out in the open on tables or close by in the drawers, easy to consult while painting; whenever an interesting idea occurred to him, he would jot it down on whatever paper was close by, a practice much appreciated today when trying to establish timeframes for his works.

In the badly abraded drawing in a Dutch private collection, most likely the next study in the series of preparatory works, Van Dyck further developed the reversal of the direction from left to right. The drawing is in an upright format and close in size tot the example now in Providence that he had discarded. The Virgin stand at the foot of het cross, partly cut off at the left. Christ, being pulled towards the right with a rope around his neck, is turning his head to look once again at his grieving mother. Simon of Cyrene is still helping with the cross.

With the version in Lille Van Dyck switched back to a horizontal format, as in the earlier example in Turin, but kept the direction towards the right. A major change is the replacement of Simon of Cyrene, who assisted Christ in carrying the cross, with a henchmen pulling Christ by the robe – an idea that reappears in the following preparatory studies and becomes prominent in the centre of the final painting in Saint Paul’s. The same Lille study also includes for the first time a soldier with outstretches arms whom Van Dyck included in The betrayal of Christ drawing in Berlin, where he is about to arrest Christ. Whereas on the Berlin sheet his arms are extended to the left, in the Lille drawing he is stretching his arms out tot he right in the same sense as in Pieter Soutman’s etching based on Van Dyck’s Betrayal of Christ study in Berlin. Could this mean that Van Dyck had Soutman’s etching at hand when he was working on Christ carrying the Cross? Would this indicate that Soutman actually created the etching after Van Dyck’s Betrayal of Christ drawing while he was still associated with Rubens’s studio in Antwerp, where Van Dyck was also present, and not after his return to Haarlem in 1628? (The one problem might be Soutmans’s Cum Privilegio; he only obtained the privilege from the Dutch States General in 1636 in Haarlem. But he apperently also used it on etchings after Rubens, potentially as early as 1619, before Rubens had secured his own privileges. According to Barret (2012: p. 45-47) states of etchings were undoubtedly published in Haarlem; however it seems probable that the print was first produced in Antwerp when Van Dyck was experimenting with the composition. Van Dyck perhaps made the Berlin drawing available to Soutman when they were active in Rubens’s studio, most likely in 1621 after Van Dyck’s return from England (Barret 2012: p. 46). Van Dyck would understandably have taken an interest in Soutman’s etching, since after all it was based on his drawing. Subsequently, Van Dyck retained this soldier in the following three compositional studies and in the final painting of Christ carrying the cross.

The study in Lille stands out from Van Dyck’s more numerous sketches in pen and ink because it is basically a brush drawing over an initial, rather messy, black chalk sketh, creating a very painterly impression. Only one other study is drawn almost exclusively with the brush, the closely related Betrayal of Christ in Berlin with the small preliminary chalk sketch of Christ carrying the Cross and the Berlin Betrayal of Christ drawing that show that Van Dyck must have been interested in the Betrayal of Christ subject first at around the same time he was painting Christ carrying the Cross for Saint Paul’s, c. 1617-18. When he returned to it later, c. 1618-20, he singled out more specifically Judas’s betrayal of Christ, which he then developed in numerous preliminary studies for his three versions of The betrayal of Christ in Bristol, Minneapolis and Madrid.

What is most special (and much appreciated) when working with Van Dyck’s drawings, in contrast to Rubens’s, is the fact that relatively few are laid down. Since Van Dyck was in the habit of using everly last space on the sheet, we are able to follow him in his natiations over several drawings and, thanks tot hem, learn how some of his paintings correlate in time.

The sequence of the drawings that Horst Vey suggested for Christ carrying the Cross continues with the refined, almost neat study in pen and inkt and wash in Chatsworth, where Van Dyck for the first time presents the scene as in the painting, but with one major difference: Christ is not looking back at his mother but in front of him. The Chatsworth drawing includes on the verso fragment of a Brazen serpent composition that not only belongs to an entirely different subject matter but is also drawn with a different quill pen and, by contrast to the Christ carrying the Cross composition on the recto, is a pure pen drawing.

Whereas Horst Vey placed the example in a Dutch private collection after the Chatsworth drawing, I believe it should precede it, since it still includes Simon of Cyrene and omits the soldier with outstretched arms. (J.G. Van gelder also placed the example in the Dutch private collection before Lille. See Van Gelder 1961: p. 3-18) Instead I propose that the next drawing in the sequence should bet he sheet formerly in Bremen (Vey 1962: no. 12, fig. 17; Brown 1991: p. 51, fig. 9), because it simplifies the Chatsworth composition. Most importantly, Christ is again looking back at his mother. The Bremen sketch is wonderfully coherent, with Van Dycks stressing the principal figures with dark outlines, at times drawn with the brush alone.

The final modello for Van Dyck’s Christ carrying the Cross, now squared for transfer, is in the Antwerp Print Room (Vey 1962: no. 13, fig. 18; Brown 1991: p. 56, no. 4, ill. In colour) and based on the drawing formerly in Bremen. Christ collapsed under the cross, is looking back at his mother, who is standing close to him, her hands folded in prayer, as in the painting. Next to her Van Dyck brought back the figure of Simon of Cyrene assisting Christ. The artist also introduced changes in the background. Still partly visible is a head that was covered with whitening but has become partly visible again under a greyish surface; the head is clearly missing in the painting. Additional changes were made in the sky at the upper left. Van Dyck added much detail to the drawing with small dots reminiscent of stippling which he introduced with the pen and dark brown ink to indicate muscle tone or bone structure. Even at this late stage he inserted a foot and part of a leg in black chalk between the legs of the man walking into the distance at the right, a foot that is indeed included in the painting, next to another one not yet added in the Antwerp drawing. Here again we find ample proof of how Van Dyck continuously added new ideas.

As a last step towards the paiting Van Dyck reverted to a working procedure he had learned from his association with the Rubens studio – that of placing a live model into the pose of an important foreground figure in the painting and drawing him or her in black chalk. Such a black chalk study with white heigthening is preserved in the Courtauld Gallery, London. Van Dyck placed a male figure in the pose of the henchman who reaches over the cross to the fallen Christ, grabbing his robe and pulling him along. In the drawing the figure is wearing a cloack that wraps around his lower left arm but leaves his right shoulder and arm bare. To find the proper position for this arm Van Dyck prepared four seperate detailed studies with differing hand positions placed next tot each other. Another sketch of the man’s left hand is included at the lower right. His left leg is angled at the knee as if resting on a step. With his right arm he is pulling on a rope – probably a studio prop. Van Dyck selected the right arm in the centre for the painting, where he introduced yet another change by extending the man’s left arm all the way to Christ’s head.

This same figure with an outstretched right arm reappears again in a similar pose at the lower right on the recto of Van Dyck’s large preliminary study in the Morgan Library, New York, for Moses and the brazen serpent painting in the Prado. In the New York drawing the man is trying to remove snakes which are engulfing a fallen worshipper. The artist must therefore have worked on Christ carrying the Cross and Moses and the brazen serpent at more or less the same time, since the verso of Christ carrying the cross in Chatsworth shows a fragment of the Brazen serpent theme that corresponds closely in execution to the large double-sided drawing in the Morgan Library, New York. The figures in the Chatworth fragment, however, are moving in the opposite direction, towards the right, and do not relate either to the New York drawing or the Prado painting, where the serpent is placed at the left.

There is a third theme Van Dyck was working on during that time, namely The entombment. As J.G. Van Gelder pointed out, the Virgin on the verso of the Berlin Betrayal of Christ not only resembles the one in the Providence drawing but also the one in Van Dyck’s drawing of The entombment, now in the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles (Vey 1962, no. 4, fig. 4; Brown 1991: p. 60, no. 6, ill. In colour (c. 1617-1618). It seems that the young Van Dyck was extremely busy after he entered Rubens’ circle. However, the Entombment studies apperently did not lead tot a painting.

With the drawings for Christ carrying the Cross, Van Dyck initiated a working procedure –namely making drawings from life for prominent figures in the foreground of his painting – that he was to use throughout his early years until the autumn of 1620, when he left Antwerp and ended his association with with Rubens. More so than Rubens Van Dyck often experimented with various formats – in Christ carrying the Cross, first horizontal then vertical before settling on the one he preferred, which in this case is almost square. He used pen and brush and ink and wash in various combinations, sometimes over black chalk or black chalk in addition to other media. The technique may change to a predominantly brush drawing, at times combined with noticeable additions in black chalk. Having his preliminary drawings always close at hand explains the repetitions of figures in some of his paintings. Van Dyck was not shy either to change the direction of the action from left to right or vice versa, as one sees repeatedly in the drawings for Christ carrying the Cross or Moses and the brazen serpent.

In contrast to Rubens, Van Dyck did not use oil sketches in preparation of paintings. Instead he preferred to develop his ideas on paper only, at times in up to seven or eight preliminary compositional drawings. They are drawn mostly in pen and brush and lighter and darker brown ink and brown wash, rarely in colour. His predilection fort he highley acidic iron gal link, which eats into the paper, has made some of them very delicate to handle. Van Dyck tended to square the final preliminary drawings or modelli for transfer to canvas, but there are exceptions where he changed his mind at the last minute. (see for example Christ crowned with thorns or Betrayal of Christ.

MANNAERTS 2014: p. 113:

Van geen enkel van zijn schilderijen bestaan er zo veel ontwerptekeningen. Niet minder dan tien zijn ervan bewaard, wat voor een uitzonderlijke documentatie zorgt over de ontstaansgeschiedenis van een baroktafereel. Was hij in zijn eerste studies al te zeer op zichzelf betrokken, dan vindt Van Dyck geleidelijk zijn plaats in de opbouw van de cyclus. De aanvankelijk horizontale compositie evolueert naar een verticale terwijl de oorspronkelijke beweging naar links, omwille van de samenhang met de chronologische lezing van de hele reeks, omslaat in een beweging naar rechts. Omdat het een rasterpatroon vertoont, wordt de tekening in het Antwerpse Prentenkabinet aangezien als het eigenlijke modello. Toch werden tijdens de uitvoering van het schilderij de houdingen van sommige figuren nog aangepast.

De voorstudies bevinden zich in de volgende collecties:

Antoon Van Dyck, Schetsen voor De Kruisdraging:

- TOPA vzw heeft ernaar gestreefd de rechten van de illustraties volgens wettelijke bepalingen te regelen. Degenen die desondanks menen zekere rechten te doen gelden, kunnen zich alsnog tot TOPA vzw wenden.

Herkomst: /

Verdere geschiedenis:

Antoon Van Dyck anders bekeken – over ‘registers en contrefeytsels, tronies en copyen’ in Antwerpse kerken en kloosters, (ttst.cat.), Antwerpen, 1999 (uitg. TOPA): p. 63-66:

In 1651 komt er verandering in de opstelling. Het schilderij van Caravaggio wordt gekozen als altaarstuk voor het nieuwe Rozenkransaltaar in de noorderdwarsbeuk. Ook wordt een nieuw koordoksaal met twee altaren gebouwd. Toen Descamps in 1753 op bezoek kwam, deed de Kruisdraging van Van Dyck dienst als altaarstuk voor het H. Kruisaltaar tegen het koordoksaal, rechts. Vandaar wellicht dat het schilderij 5 cm korter is dan de veertien andere.

Of deze toestand reeds uit 1651 dateert is niet met zekerheid te weten, maar bij het bezoek van Nicodemus Tessin in 1687 had de verandering reeds plaatsgevonden. De toestand bleef ongewijzigd tot het begin van de jaren 1770. Mols vermeldt in 1774 dat De Kruisdraging sedert kort weer op zijn oorspronkelijke plaats hangt.

[…]

Wanneer in 1777 in opdracht van de Oostenrijkse overheid een inventaris wordt gemaakt van alle kunstwerken die in aanmerking komen voor een museum, worden voor de Rozenkransreeks in de St.-Pauluskerk enkel twee schilderijen als uitmuntend aangeduid: De Geseling van Rubens en De Kruisdraging van Antoon Van Dyck.

In 1794 werd het stuk naar Parijs vervoerd. Het zou pas in 1816 teruggeplaatst worden in de St.-Pauluskerk, die ondertussen parochiekerk geworden was.

SIRJACOBS 2001:

‘Opgevorderd door de Fransen in 1794, vervoerd naar het Louvre, teruggehaald na de slag van Waterloo, in 1816.’

VERGARA Alejandro en LAMMERTSE Friso, The young Van Dyck, Londen, 2013: p. 149.

The painting hung in Saint Paul’s Church until August 1794, when it was taken to Paris by French troops and exhibited at the Musée du Louvre. After it was returned on 5 December 1815, it remained for some time in the old Franscan friary of Antwerp before its definitive return tot he church of the Dominicans in June 1816. (PIOT 1883, NIEUWENHUIZEN 1962: P. 79, 82; VLIEGHE 1971, Notice des Tableaux 1799, no. 251 and Notice des Tableaux 1816, no. 24)

MANNAERTS – toevoeging 2018:

Na de herovering van Antwerpen op de Oostenrijkers in 1794 eist de Franse bezetter oorlogsbuit: niet alleen geldelijk, maar ook in natura. Omwille van de roem van de kunstenaar wordt dit schilderij samen met de andere werken van Rubens en van Jordaens in deze kerk in dat jaar als oorlogsbuit in beslag genomen en meegenomen naar het Musée Central des Arts te Parijs (gevestigd in het Louvre-paleis).

Na de nederlaag van Napoleon keert het naar Antwerpen terug in december 1815. Na expositie in het lokale museum in 1816 wordt het teruggeplaatst op zijn oorspronkelijke bestemming in de Sint-Pauluskerk.

In 1794 wordt het naar Parijs vervoerd, om hier na de Franse nederlaag, in 1816 terug te keren.

Restauraties: Het schilderij werd in 1970 gerestaureerd door het KIK (bron: JANSSENS 1971)

Tentoonstellingen:

Tentoonstellingen van voorstudies en schilderij:

Antwerpen 1899 (nr. 11); Antwerpen 1949 (nr. 1); Antwerpen-Rotterdam 1960 (nr. 6-11); Princeton 1979 (p. 38-49, nr. 1-5); Ottawa 1980 (nr. 16-18), fig. 38-39); New York 1991 (p. 48-59); Antwerpen 1991 (nr. 21); Antwerpen 1999A (nr. 7); Prado, Madrid, 2013

A) Andere kunstwerken die dit kunstwerk hebben beïnvloed:

- Dit kunstwerk is geïnspireerd door:

VERGARA Alejandro en LAMMERTSE Friso, The young Van Dyck, Londen, 2013: p. 151:

In any case, it is generally accepted that Rubens’s sketch, whether created specifically fort he series of the Rosary or not, was both a starting point and a source of inspiration for Van Dyck. There are details common to both compositions, such as the vivid colouring of the figures, and the use of the sticks and halbards with which Christ is beaten as a vehicle for generating expressive diagonals. The pictures also share specific motifs, such as the inclusion of an executioner who is dragging Christa long with his arm. Indeed, the prominence of this arm recalls a motif used by Rubens in a number of his compositions (There is an oil sketch of about 1609-10 in the Art Institute of Chicago showing The capture of Samson by the Philistines, where Rubens employs similar motifs (D’HULST en VANDENVEN 1989, no. 32; HELD 1980, I: p. 433, no. 313; II, fig. 310. The links between this composition and Van Dyck’s picture were pointed out in Van Gelder 1961, p. 16, though in relation to a picture on the same subjecct at the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, a piece from Rubens’s workshop painted in about 1620 on the basis of a drawing), and Van Dyck’s concern with the detail is clear from one of his preparatory drawings. There are other links between Christ carrying the Cross and Rubens. Another example is the executioner whose back is turned to the viewer. This exercise in anatomical drawing, which is similar to Van Dyck’s figure of Samson in the picture Samson and Delilah (As is put forward in the essay by Friso Lammertse and Alejandro Vergara in this publication), is based on classical sculptures like the Hermaphrodite (Rome, Galleria Borghese), known to Van Dyck through drawings by Rubens (See the drawing at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, inv. no. 1972.118.286; Jaffé 1977b, p. 81, fig. 290; Held 1986, p. 81-82, no. 38, ill. 37). The sword carried by the executioner seems to be the same one as the one used by the protagonist of Decius Mus relating his dream (Vienna, Sammlungen des Fürsten von und zu Liechtenstein) (Inv. no. GE47. See Kräftner, Seipel and Trnek 2004: p. 136, no. 30).

Together with the influence of Rubens, Van Dyck’s picture also reflects other widely known representations of the same subject. Examples include the famous engraving by Martin Schongauer (Hollstein German, XLIX: L p. 66, no. 26) and, above all, the print by Dürer for the series of the Great Passion (See Schoch, Mende and Sherbaum 2001, II, p. 197, no. 160). The painting coincides with both these prints in the movement of the procession from left to right, the use of a female character shown in profile to close off the composition on the left, and the presence of an executioner with a similar compositional function on the right. There are also similarities in specific details, such as the way Christ’s head is turned. The bearded character in the picture, who is about to beat Christ with a stick, is performing the same action as one of the executioners in Dürer’s engraving, although he is shown facing the opposite way.

Despite all these possible influences, Van Dyck’s painting demonstrates some of the chief characteristics of his youthful manner, such as a taste for coarse character types, sinuous outlines and his interest in rendering the intensity and pathos of a story, which he was to maintain in his later work.

- Dit kunstwerk is gekopieerd naar: /

B) De invloed van dit kunstwerk op andere kunstwerken:

- Dit kunstwerk is in prent omgezet (door):

Gravure door Cornelis I Galle

O.a. Rijksmuseum: http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.114242

– Alexander Voet, kopergravure, …

– J. Falck

Antoon Van Dyck anders bekeken – over ‘registers en contrefeytsels, tronies en copyen’ in Antwerpse kerken en kloosters, (ttst.cat.), Antwerpen, 1999 (uitg. TOPA): p. 63-66:

Later werd de compositie door Cornelis Galle de Oude en J. Falck in prent gebracht.

VERGARA Alejandro en LAMMERTSE Friso, The young Van Dyck, Londen, 2013: p. 149:

From very early on, the painting was reproduced in prints which identified it as the work of Van Dyck.

- Dit kunstwerk is inspirerend voor:

Blijkbaar genoot het schilderij appreciatie, en werkte het inspirerend voor menig schilder:

- Christus valt onder het kruis, anoniem, tweede kwart 17de eeuw, olieverf op paneel, 114 x 82 cm. (Onze-Lieve-Vrouwe-kathedraal, Antwerpen, inv. nr. 970)

bron: Inventaris Kunstpatrimonium Provincie Antwerpen, Onze-Lieve-Vrouwe-kathedraal, 1996, cat.nr. 970

bron: Antoon Van Dyck anders bekeken – over ‘registers en contrefeytsels, tronies en copyen’ in Antwerpse kerken en kloosters, (ttst.cat.), Antwerpen, 1999 (uitg. TOPA): : p. 63-66.

- Versie Jan van den Hoecke

– Schilderij of tekening Jan van den Hoecke (niet in catalogi Van Dyck; website Rijksmuseum spreekt over schilderij)

http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.338260

– De Kruisdraging, Alexander Voet (1613-1689/1690) naar Jan van den Hoecke (Ioannes van Hoeck, 1611-1651), kopergravure

https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/nl/collectie/RP-P-1908-3631

- Bron: VLIEGHE H., Nicht Jan Boeckhorst sondern Jan van den Hoecke, Westfalen, 1990: p. 175-177.

– Grisaille naar de gravure van Alexander Voet

========

– Jezus valt onder het kruis, (statie 8 van de kruisweg in zuiderbeuk), (Sint-Katelijnekerk, Mechelen)

== = = = Navolgingen nog verder te onderzoeken = = = = =

– exemplaar in StichtingTerninck, Antwerpen

- bron: Inventaris Kunstpatrimonium Provincie Antwerpen, Onze-Lieve-Vrouwe-kathedraal, 1996, cat.nr. 970

– exemplaar (olieverf op doek, 96 x 76 cm.), dat zich in 1928 in de galerij Samuel Hartveld te Antwerpen bevond

- bron: Inventaris Kunstpatrimonium Provincie Antwerpen, Onze-Lieve-Vrouwe-kathedraal, 1996, cat.nr. 970

- Dit kunstwerk is gekopieerd (door):

Peter I Thijs (1624-1677), 1645-1677

Antoon Van Dyck anders bekeken – over ‘registers en contrefeytsels, tronies en copyen’ in Antwerpse kerken en kloosters, (ttst.cat.), Antwerpen, 1999 (uitg. TOPA): p. 63-66:

Ondertussen werd voor de Rozenkranscyclus een kopie van De kruisdraging gemaakt. Deze kopie werd volgens een 18de-eeuwse beschrijving van de Antwerpse kerken door een zekere dominicaan Thijssens geschilderd. In de lijsten van de Neder-landse dominicanen komen inderdaad twee paters Thijssens voor, maar in de 18de eeuw, en zonder enige aanduiding dat zij de schilderkunst zouden beoefend hebben. De verschillende werken die aan deze – fictieve – schilder toegeschreven werden, blijken allen van de hand van Peter Thijs de Oude (1624-1677), een bekende van Dyck kopiïst, te zijn. Dit situeert alleszins het ontstaan van de kopie tussen 1645 (zijn meesterschap) en 1677 (zijn overlijden). …

Drie kopieën verschenen op de kunsthandel, maar de vraag is of één ervan te vereenzelvigen is met de kopie van Thijs. Volgens Jacob de Wit was er alleszins in de 18de eeuw een goede kopie te vinden in het Terninck-instituut.

ROBBROECKX Mark, Antoon Van Dyck en de Antwerpse Sint-Pauluskerk in Sint-Paulus-Info, nr. 67, 1999: p. 1531, noot 23:

- een drietal andere kopieën, waarvan de kopiïsten niet gekend zijn

Archief van de Sint-Pauluskerk, register I, nr. 8-9

Antwerpsch Archievenblad 22, p. 120

Stadsarchief Antwerpen: Not. J. Placquet, nr. 2846.

Stadsarchief Antwerpen, Anoniem, Beschrijvinghe van de cloosters, autaeren, epitaphiën, schilderijen en beelden ende andere variteyten in de stadt van Antwerpen, 19e-eeuws, privilegekamer, nr. 197.

OPGELET: indien u een andere taal gekozen hebt, zullen de titels van deze boeken en artikels helaas automatisch mee vertaald worden!

U kan zelf de bibliografie sorteren op jaartal of op auteur.

Eerst de bibliografie over het schilderij zelf

@Jaar | @Auteur | Referentie |

1999 | BAISIER Claire | Antoon van Dijck, de Kruisdraging, Sint-Pauluskerk in Antoon Van Dyck anders bekeken - over ‘registers en contrefeytsels, tronies en copyen’ in Antwerpse kerken en kloosters, (ttst.cat.), Antwerpen, 1999 (uitg. TOPA): p. 63-66. |

2004 | BARNES Susan J. e.a. | Van Dyck. A complete catalogue of the paintings, New Haven en Londen, 2004: nr. l.25. |

1971 | BAUDOUIN Frans, en D' HULST, Roger-A | Rubens en zijn tijd: tekeningen uit Belgische verzamelingen: tentoonstelling naar aanleiding van het 25-jarig bestaan van het Rubenshuis als museum (tent.cat.), Antwerpen, 1971: p. 38-39. |

1672 | BELLORI Gio. Pietro | Le vite de' pittori, scultori et architetti moderni, Rome, 1672 (ed. 1976): p. 272. |

1774 | BERBIE Gerard | Description des principaux ouvrages de peinture et sculpture; actuellement existans dans les églises, couvens & lieux publics de la ville d'Anvers ..., Antwerpen 1774: p. 68-69. Google-Books |

1765 |

| Beschryvinge der bezonderste werken van de schilder-konste ende beeldhouwerye, nu ter tyd zynde in de kerken, kloosters, ende openbaere plaetsen der stad Antwerpen, in het licht gegeêven tot profijt der Reyzers. Op nieuws overzien, verbetert ende vermeerdert, Antwerpen (drukker BERBIE Gerardus), 1765: p. 74. |

1981 | BOGAERTS, A.M. | Repertorium der dominicanen in de Nederlanden I: Antwerpen- Lier in Bouwstoffen voor de geschiedenis der dominicanen in de Nederlanden, nr. 19, Leuven; 1981: p. 326-327. |

1899 | BREDIUS Abraham | De Van Dyck-tentoonstelling, Den Haag, 1899: p. 3-4. |

1999 | BROWN Christopher | De kruisdraging in BROWN Christopher en VLIEGHE Hans, Van Dyck 1599-1641, (ttst.cat., Antwerpen en Londen), Gent, Amsterdam, 1999: p. 104-107. |

1982 | BROWN Christopher | Van Dyck, Oxford, 1982: p. 40. |

1991 | BROWN Christopher | Van Dyck. Tekeningen, tent. cat. New York 1999, vertaald uit het Engels, Mercatorfonds Antwerpen, 1991: p. 48-59. |

1906 | CUST L. | Anthony van Dyck in Great masters in painting and sculpture, Londen, 1906: p. 14. |

1900 | CUST Lionel | Anthony van Dyck: an historical study of his life and works, Londen, 1900: p. 11, 233, nr. 5. |

1783 | DE GOMICOURT Derival | Le voyageur dans les Pays-Bas Autrichiens, ou Lettres Sur l'état actuel de ces Pays, dl. III (eerste helft), Amsterdam, 1783: p. 430-431. |

1991 | DE PAUW Carl | Antoon Van Dyck. De kruisdraging in Antoon Van Dyck (1599-1641) & Antwerpen, ttst.cat., Antwerpen, 1991: p. 152-153. |

1999 | DE PAUW Carl en LEMAN Steven | Anton van Dyck, Graphiken Andernacher Beiträge, 14, Andernach 1999 (n.a.v. 20 jaar verbroedering met Ekeren): p. 56-57. |

1910 | DE WIT Jacobus, DE BOSSCHERE J. | De kerken van Antwerpen. Schilderijen, beeldhouwwerken, geschilderde glasramen, enz., in de XVIIIe eeuw beschreven door Jacobus de Wit. Met aantekeningen door J. De Bosschere en grondplannen, Antwerpen, 1910: p. 57, 148. |

1934 | DELACRE Maurice | Le dessin dans l’oeuvre de Van Dyck, Mémoire de l’Académie Royale de Belgique. Classe des Beaux-Arts, Brussel, 1934: p. 90-111. |

1938 | DELEN A.J.J. | Catalogue des dessins anciens. Ecoles flamande et hollandaise, Brussel, 1938: p. 106. |

1931 | DELEN Ary J.J. | Un dessin inconnu d'Antoine van Dyck in Revue belge d’Archéologie et d’Histoire de l’ art, I, Brussel, juli 1931: p. 193-199. |

1753 | DESCAMPS Jean Baptiste | La vie des peintres flamands, allemands et hollandais, Parijs, 1753: p. 23. |

1769 | DESCAMPS Jean Baptiste | Voyage pittoresque de la Flandre et du Brabant avec des réflexions relativement aux arts & quelques gravures, Parijs, 1769: p. 191, 202. |

1960 | D'HULST Roger-Adolf en VEY Horst | Antoon van Dyck: Tekeningen en olieverfschetsen (tentoonstelling Antwerpen, Rubenshuis, 01.07 - 31.08.1960; Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, 10.09 - 06.11.1960), Antwerpen, 1960: p. 42-47. |

1909 | DIMIER L. | Reynolds discours sur la peinture et voyages pittoresques, Parijs; 1909: p. 386. |

1899 | FIERENS-GEVAERT A. | Hommage à Van Dyck. La technique de Van Dyck, Antwerpen, 1899: p. 61. |

2013 | FLOOR Maaike | Sint-Pauluskerk. Paneel Van Dyck is weer thuis. Kruisafdraging hing vijf maanden in Museo del Prado in Madrid, in Gazet Van Antwerpen, 9 april 2013. |

1873 | GÉNARD P. | Verzameling der graf- en gedenkschriften van de provincie Antwerpen, dl. V, 1873: p. 100, 112, 119, 147, 150, 184. |

1931 | GLÜCK Gustav | Van Dyck: des Meisters Gemälde (Klassiker der Kunst, XIII), Stuttgart-Berlijn, 1931: p. 518, nr. 11 |

1882 | GUIFFREY Jules | Antoine Van Dyck: sa vie et son oeuvre, Parijs, 1882: p. 15-16 en nr. 101. |

1991 | HELLEMANS Marijke | Tentoonstelling in Stedelijk prentenkabinet. Rondom Rubens. Tekeningen en prenten uit eigen verzameling in Stad Antwerpen. Cultureel Jaarboek, 1991: p. 49-50. |

s.d. | HOLLSTEIN | Hollstein’s Dutch and Flemish etchings, engravings and woodcuts ca. 1450-1700, dl. 6, Amsterdam, z.d.: p. 114, nr. 204 en 225. |

1979 | JANSEN Jaak | Fotorepertorium van het meubilair van de Belgische bedehuizen. Provincie Antwerpen, Kanton Antwerpen V en VI, Brussel-Antwerpen, 1979: p. 107-108. |

1971 | JANSSENS Aloïs | Sint-Pauluskerk te Antwerpen en haar kunstbezit, 1971: p. 101. |

1971 | JANSSENS Aloïs | Sint-Pauluskerk te Antwerpen en haar kunstbezit, Antwerpen, 1971: p. 101. |

1939 | KNIPPING B. | De iconografie van de Contra-Reformatie in de Nederlanden, I, Hilverssum, 1939-1940: p. 280. |

1828 | KUNSTLE K. | Ikonographie der christlichen Kunst, I, Freiburg i. Br., 1928: p. 443, 445. |

1975 | LARSEN Erik | La vie, les ouvrages et les élèves de Van Dyck. Manuscrit inédit des archives de Louvre. Par un auteur anonyme, 1769/91, (Académie Royale de Belgique, Mémoires de la classe des Beaux-Arts, 2e série, XIV), Brussel, 1975: p. 48. |

1980 | LARSEN Erik | Alle tot nu toe bekende schilderijen van Van Dyck, Lekturama, Rotterdam, 1980: nr. 252. |

1988 | LARSEN Erik | The Paintings of Anthony van Dyck, Freren, 1988: p. 113, nr. 269. |

2014 | MANNAERTS Rudi | Sint-Paulus. De Antwerpse dominicanenkerk, Antwerpen, 2014: p. 113-115. |

2008 | MANNAERTS Rudi | Sint-Pauluskerk te Antwerpen, Antwerpen 2008: p. 22. |

1851 | MARIETTE Pierre-Jean | Abecedario de P.J. Mariette et autres notes inédites de cet amateur sur les arts et les artistes. Ouvrage publié d’après le manuscripts autographes, conservés au Cabinet des Estampes de la Bibliothèque Imperiale, ed. Philippe de Chennevières en Anatole de Montaiglon, Parijs, 1851-60: dl. II: p. 181. |

1979 | MARTIN John Rupert en FEIGENBAUM Gail | Van Dyck as religious artist, tent. cat. Princeton, University Art Museum, Princeton, 1979: p. 38. |

1763 | MENSAERT G.P. | Le peintre amateur et curieux ou description générale des tableaux des plus habiles maîtres, qui font l'ornement des églises, couvents, abbayes, prieurés & cabinets particuliers dans l'étendue des Pay-Bas Autrichiens: ouvrage tres-utile, Brussel, 1763: p. 200-202. |

1994 | MOIR Alfred | Anthony Van Dyck, New York, 1994: p. 11-12. |

1987 | PERSOONS Guido | Zeventiende eeuwse Kerstnacht (naar P.P. Rubens) door Peter Thijs de Oude (atelier?) met glans hersteld in Sint-Paulus-Info; 1987: p. 421-425. |

1950 | PUYVELDE Léo | Van Dyck, Brussel, 1950: p. 123-124. |

1957 | RÉAU Louis | Iconographie de l’art chétien, II, II: Nouveau testament, Parijs, 1957: p. 463-464. |

1996 | REYNOLDS Sir Joshua | A journey to Flanders and Holland, uitg. Harry Mount, Cambridge, 1996: p. 53. |

1999 | ROBBROECKX Mark | Antoon Van Dyck en de Antwerpse Sint-Pauluskerk in Sint-Paulus-Info, nr. 67, 1999: p. 1530-1533. |

1972 | ROBBROECKX Mark | De vijftien rozenkransschilderijen van de Sint-Pauluskerk te Antwerpen, onuitg. Lic. Verhandeling, Rijksuniversiteit Gent, 1972: p. 17-18, 28-29, 86-92. |

1906 | ROOSES M. | Jordaens. Leven en werken, Amsterdam-Antwerpen, 1906: p. 10 (documenten i.v.m. de opdracht). |

1905 | ROOSES Max | Rubens' Leben und Werke, Stuttgart, 1905: p. 316. |

1900 | ROOSES Max | Vijftig meesterwerken van Antoon Van Dyck in photogravure afgebeeld naar de schilderijen tentoongesteld te Antwerpen in 1899: beschreven, historisch toegelicht en met eene levensschets van den kunstenaar voorzien, Antwerpen, 1900: p. 2-3. |

1928 | ROSENBAUM Heinrich | Der junge Van Dyck (1615-21), München, 1928: p. 52-53. |

1909 | SCHAEFFER E. | Van Dyck. Des Meisters Gemälde (Klassiker der Kunst, XIII), Stuttgart-Leipzig, 1909: p. 496, nr. 17. |

1993 | SIRJACOBS Raymond en COOLEN Guido | Antwerpen Sint-Pauluskerk: de Vijftien Mysteries van de Rozenkrans, Antwerpen, 1993: p. 38. |

2004 | SIRJACOBS Raymond | Antwerpen Sint-Pauluskerk. Rubens en de Mysteries van de Rozenkrans, Boechout, 2004 (?): p. 58. |

1999 | SIRJACOBS Raymond | Sint-Paulus-Info, nr. 67, Jaarboek 1999 (n.a.v. internationaal Van Dyckjaar): p. 1530-1533. |

1999 | SIRJACOBS Raymond | Sint-Pauluskerk Antwerpen, Antwerpen, 1999: 36 en 178. |

2001 | SIRJACOBS Raymond | Sint-Pauluskerk Antwerpen. Historische gids, 2de herw. uitg., Boechout, 2001: p. 44-45. |

1829 | SMITH John | A catalogue raisonné of the works of the most eminent Dutch, Flemish and French painters, Londen, 1829: p. 111, nr. 408. |

1900 | UPMARK G. | Ein besuch in Holland (1687) aus den Reiseschilderungen des schwedischen Architecten Nicodemis Tessin d.j.: p. 204. |

1883 | VAN DEN BRANDEN F. Jos | Geschiedenis der Antwerpsche schilderschool, Antwerpen, 1883: p. 700. |

1943 | VAN DEN WIJNGAERT Frank | Antoon Van Dyck, Antwerpen, 1943: p. 25-26. |

1771 | VAN DER SANDEN Jacob | Oud Konst-toneel van Antwerpen, Antwerpen, 1771, dl. 2 |

1949 | KMSKA | Van Dyck Tentoonstelling, tent.cat. Antwerpen Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerpen, 1949: p. nr. 1. |

1961 | VAN GELDER J.G. | Van Dycks Kruisdraging in de St.-Pauluskerk te Antwerpen in Koninklijke Musea voor Schone Kunsten. Bulletin 1-2 (1961): p. 3-18. |

2006 | VAN HOUT Nico | Schilderkunstige kanttekeningen bij de Rozenkransreeks in de Sint-Pauluskerk te Antwerpen in Munuscula amicorum. Contributions on Rubens and his Colleagues in Honour of VLIEGHE Hans, K. Van der Stighelen (ed.), 2006: p. 458-461. |

1949 | VAN PUYVELDE Leo | L'atelier et les collaborateurs de Rubens, Brussel, 1949: p. 248-249. |

1933 | VAN PUYVELDE Leo | Les débuts de Van Dyck, Brussel, 1933: p. 5. |

2013 | VERGARA Alejandro en LAMMERTSE Friso | The young Van Dyck, Londen, 2013: p. 149-151. |

1962 | VEY Horst | Die Zeichnungen Anton Van Dycks, Brussel, 1962: p. 4, 59, 79-87, 148-149, nr. 7-15. |

1958 | VEY Horst | Van-Dyck-Studien, Keulen, 1958: p. 11-35. |

1971 | VLIEGHE H. | Het verslag over de toestand van de in 1815 uit Frankrijk naar Antwerpen teruggekeerde schilderijen in Jaarboek KMSKA, 1971: p. 281. |

1906 | VON BODE Wilhelm | Rembrandt und seine Zeitgenossen, Leipzig, 1906: p. 261. |

1984 | WUYTS Leo | De vijftien schilderijen van de Rozenkrans, nr. 9 De Kruisdraging in Sint-Paulus-Info, jg. 2, nr. 18, 1984: p. 118. |

En hier de algemene bibliografie over de voorstudies

@Jaar | @Auteur | Referentie |

1672 | BELLORI Gio. Pietro | Le vite de' pittori, scultori et architetti moderni, Rome, 1672 (ed. 1976): p. 254. |

1921 | OLDENBOURG Rudolf en ROSENBERG Adolf | P. P. Rubens: des Meisters Gemälde in 538 Abbildungen, Stuttgart, 1921: p. 419. |

1931 | GLÜCK Gustav | Van Dyck: des Meisters Gemälde in 571 Abbildungen, Stuttgard, 1931: p. 11. |

1979 |

| Tentoonstellingscatalogus Princeton 1979: p. 38-39. |

1980 | HELD Julius Samuel | Oil sketches of Peter Paul Rubens: A Critical Catalogue, 1980, New Yersey: I, 473, nr. 344, nr. 345. |

1990 | TERÉZ GERSZI | in Da Leonardo a Rembrandt, disegni della Biblioteca Reale, Turijn 1990: nr. 140. |

2013 | VERGARA Alejandro en LAMMERTSE Friso | The young Van Dyck, Londen, 2013: p. 138-148. |

De bibliografie over de afzonderlijke voorstudies staat telkens op de pagina van die voorstudie, te benaderen via de pagina geschiedenis van het object

Kunstenaar: Antoon Van Dyck (1599-1641)

Antoon Van Dyck anders bekeken – over ‘registers en contrefeytsels, tronies en copyen’ in Antwerpse kerken en kloosters, (ttst.cat.), Antwerpen, 1999 (uitg. TOPA): p. 63-66:

Er wordt wel eens geopperd dat Antoon Van Dyck pas op 11 februari 1618 vrijmeester van de St.-Lucasgilde werd. Nochtans is bekend dat hij minstens sinds 1616 een eigen atelier had en voor eigen rekening opdrachten vervulde. Maar het is goed mogelijk dat de opdracht aanvankelijk aan Rubens werd toevertrouwd, en dat deze laatste ze aan Van Dyck doorgaf.

SIRJACOBS 2001:

Eén van de eerste werken van Van Dyck

VERGARA Alejandro en LAMMERTSE Friso, The young Van Dyck, Londen, 2013: p. 149:

From very early on, the painting was reproduced in prints which identified it as the work of Van Dyck. It was therefore included in the first biographies of the artist and in the historical guide to Antwerp, which generally held it to be one of his earliest works. (LARSEN 1975, p. 48; DE WIT 1748: p. 55-57; MENSAERT 1763, I: p. 202-203; DESCAMPS 1769: p. 191). In 1672, Bellori referred to the painting at the Dominican church as one of the finest works Van Dyck produced in the style of Rubens during the time he was his pupil. (BELLORI 1672: p. 254). For these reasons, the attribution to Van Dyck has never been in doubt.

Because this was an important set of paintings, it is remarkable that Van Dyck, then a young man of barely 18, should have been included among the leading Antwerp artists selected for the work, among them Hendrik van Balen, Rubens, Cornelis de Vos and Frans Francken. In this case, it is worth speculating on the possible influence both Rubens, because of his links with the artist, and Hendrik van Blaen, his former master. One clue as to the nature of Van Dyck’s participation may be inferred from the prices paid for the works. Only Van Balen, who was paid 216 florins for the painting, received more money than Van Dyck, whose sum of 150 florins made him better paid than established artists like De Vos and Francken. Remarkable too is the fact that the same amount was paid to Rubens and Jacob Jordaens for their contributions to the series. This raises the possibility that the paintings by Van Dyck and Jordanes, who at the time also worked for Rubens, were originally commissioned from Rubens himself, or negotiated by him, and so were allotted the same price as the one that he personally executed.

The possibility of an intitial commission from Rubens was raised by Horst VEY with regard tot an oil sketch of the same subject painted by Rubens in about 1615-16, and closely related to one of Van Dyck’s preparatory drawings. Vey supposed that the sketch had subsequently been handed over to Van Dyck along with the commission. (VEY 1962: p. 85. For the sketch by Rubens (Vienna, Academie der Bildende Künste, Gemäldegalerie, inv. no. 625), see HELD 1986: p. 474, no. 344). However Christopher BROWN has expressed doubts about this possibility because the scene in the sketch is reversed in the final painting, where it coincides with the direction taken by processions as they moved past the paintings in the church. The iconographic changes between the sketch by Rubens and the final painting by Van Dyck are also significant, especially the exclusion of Saint Veronica and the importance acquired by the figure of the Virgin. (DE POORTER in: BARNES e.a. 2004; p. 42. It has also been proposed that the whole cycle might have been produce dunde the general supervison of Rubens (VAN HOUT, 2006: p. 472).

Datering: tussen 1615 en 1620; zie datering van de gehele Rozenkransreeks

Antoon Van Dyck anders bekeken – over ‘registers en contrefeytsels, tronies en copyen’ in Antwerpse kerken en kloosters, (ttst.cat.), Antwerpen, 1999 (uitg. TOPA): p. 63-66:

De datering van de reeks in 1617 is niet uit archivalische documenten gekend, maar door een 19de-eeuws opschrift op de luiken die ca. 1818-24 aan het schilderij van Rubens werden toegevoegd. Stilistisch is deze datering aanvaardbaar voor alle vijftien de werken. Er wordt wel eens geopperd dat Antoon Van Dyck pas op 11 februari 1618 vrijmeester van de St.-Lucasgilde werd. Nochtans is bekend dat hij minstens sinds 1616 een eigen atelier had en voor eigen rekening opdrachten vervulde. Maar het is goed mogelijk dat de opdracht aanvankelijk aan Rubens werd toevertrouwd, en dat deze laatste ze aan Van Dyck doorgaf.

VERGARA Alejandro en LAMMERTSE Friso, The young Van Dyck, Londen, 2013: p. 149-151:

On the nineteenth-century frame of the picture that Rubens made for the cycle, The Flagellation of Christ, there is an inscription which claims that it was paintedin 1617.This inscription probably refers to earlier knowledge, thus giving an approximate date for the commission. This is perhaps too early for Van Dyck’s paintin, since he dit not become a master of the Guild of Saint Luke until 11 February 1618, and presumably was not allowed to sell pictures before that date. Christ carrying the Cross is therefore likely to have been painted shortly after the presumed date of Rubens picture.

Stijl: barok

VERGARA Alejandro en LAMMERTSE Friso, The young Van Dyck, Londen, 2013: p. 139:

Christ carrying the Cross is one of the earliest paintings by the young Anthony van Dyck, still in ‘his early Rubensian style’ to quote Giovan Pietro Bellori’s Vite of 1672, and the only one with an approximite date.

Materiaal: olieverf op paneel

Afmetingen: 214 x 163 cm.

Het werk werd aan de boven- en aan de onderzijde ongeveer 8 cm. ingekort omdat het later in de 17de eeuw op het Heilig Kruisaltaar werd gehangen.

BALaT KIK-IRPA, RKD: 211 x 161,5 cm.

Inventarisnr.:

SIRJACOBS, Inventaris, dl. I, Sint-Paulus-Info, nr. 70, 2006: p. 1805, nr. E9.

DONNET: PA.029.E0009

Locatie: Voorheen aan de noordbeuk (bij de Mysteries van de Rozenkrans). Het werd later in de 17de eeuw op het Heilig Kruisaltaar gehangen.

DE WIT 1910:

Volgens DE WIT (1910: p. 57) hing in de H. Kruiskapel het origineel en op de vroegere plaats bij de Mysteries van de Rozenkrans een kopie van Van Dyck. Maar direct daarna wordt vermeld dat het originele schilderij weer in de noordbeuk zou hangen (bij de Mysteries) en dat de kopie nu in het altaar hing.